Advertisement

Weekly Rice Market

(Indicative Quotes)

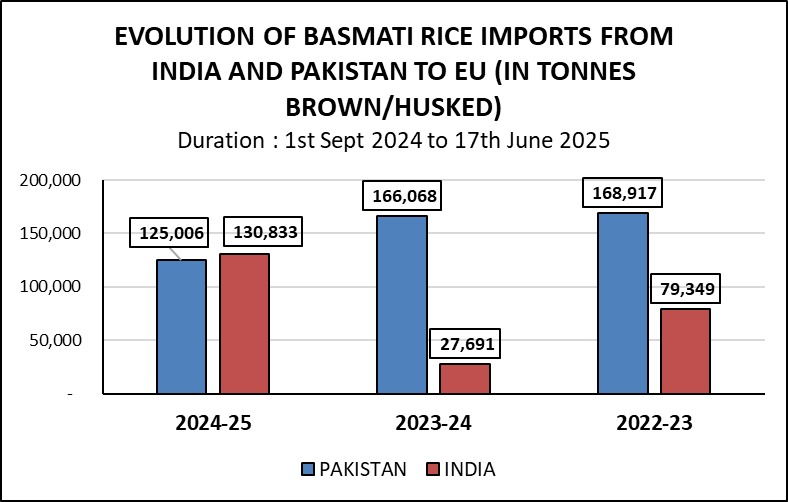

Basmati Rice

Basmati Rice | Indicative Quotes | Updated Weekly

Global Market | White Rice

White Rice | Indicative Quotes | Updated Weekly

| Origin | Type of Rice | Variety Name | Broken | Price | Change | High | Low |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | Milled White Rice | Long Grain | 5% | $383 | -2 | $496 | $380 |

| Pakistan | Milled White Rice | Long Grain | 5% | $394 | -2 | $640 | $381 |

| Pakistan | Milled White Rice | Long Grain | 5% | $590 | -2 | $613 | $488 |

| Thailand | Milled White Rice | Long Grain | 5% | $406 | -10 | $669 | $399 |

| Thailand | Milled White Rice | Long Grain | 5% | $596 | -10 | $659 | $469 |

| U.S | Milled White Rice | Long Grain | 4% | $662 | -3 | $818 | $662 |

| U.S | Milled White Rice | Long Grain | 4% | $798 | -3 | $798 | $708 |

| Vietnam | Milled White Rice | Long Grain | 5% | $387 | -4 | $657 | $387 |

| Vietnam | Milled White Rice | Long Grain | 5% | $579 | -4 | $667 | $445 |

News

Asia rice: India p...

Reuters Indian rice prices remained unchanged from the previous week as demand remained subdued and supplies stayed on the higher side, while Thai rates fell pressured by a

MAPCO exports over...

Global New Light of Myanmar Myanmar Agribusiness Public Corporation (MAPCO) shipped 7,302 tonnes of rice to five foreign countries in the first quarter of the current financial

Cambodia exports n...

The Cambodian Rice Federation (CRF) reported that during the first six months of 2025, Cambodia exported 387,070 tonnes of milled rice, valued at approximately $283 million. The

Maximum retail pri...

By: Jordeene B. Lagare – Reporter MANILA, Philippines – Starting July 16, the maximum suggested retail price (MSRP) for imported rice will be lowered to P43 a kilo from

India gets two gen...

Source: Mongabay In a step towards strengthening food security amid rising climate pressures, researchers at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) and the Indian

Rains, rice planti...

In a matter of two weeks, kitchen essentials have become doubly dear, according to the Kalimati Fruits and Vegetable Market. The Kathmandu Post KATHMANDU – With monsoon

Country’s ri...

FE REPORT As of the first day of the current fiscal year, the stock of rice in the country has increased to 1.541 million tonnes from the previous year’s 1.473 million

Favorable weather ...

Source: World Grain More favorable weather conditions have improved the outlook for 2024-25 milled rice and corn production in the Philippines, according to a report from the

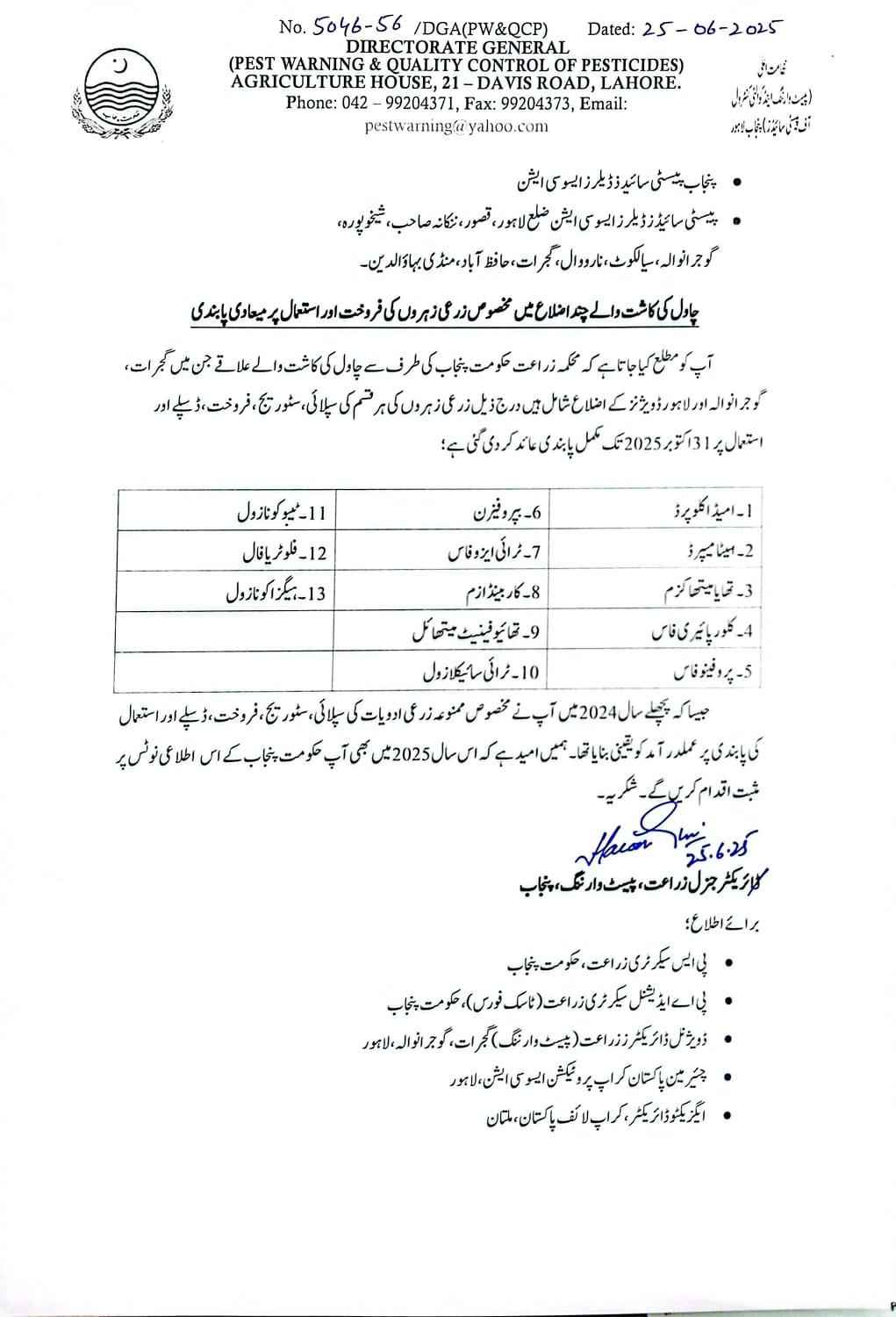

Pesticide registra...

Large number of registration cases remain pending with regulatory authority. By Ghulam Abbas ISLAMABAD: Pakistan’s agriculture sector is facing growing uncertainty as

Featured Registered Companies

RNT Tube

Pakistan’s Rice Exports Resilient Amid India’s Subsidized Competition | Dawn News English

June 25, 2025

Statistics

Sustainable Rice

Farmers Place

Forex Rates

Open Market Forex Rates

Updated at:

From | ||

|---|---|---|

To | ||

| Countries | Currency | Spot Rate |

Enjoyed the read?

Join our monthly newsletter for helpful tips on how to run your business smoothly