Tags

Rice farmers join revolution for low emissions, high profits

Though puzzled by jargon like carbon emissions and credits, many rice farmers have been part of a clean agriculture project for over a decade, attracted by its high profits.

Vo Minh Chieu was skeptical when first approached to trial a new type of rice which promised low levels of carbon emissions.

He did not expect it to result in an agricultural revolution in the Mekong River Delta 12 years later.

Chieu, director of 7B Canal Cooperative in the delta’s Kien Giang Province, met with academics from Can Tho University in 2012.

“When told about low-emission rice farming, I did not really understand it and did not think that such a thing would be effective,” he says.

The province Agriculture Extension Center was looking for a site to pilot the project, and chose the 7B Canal Cooperative due to its centralized irrigation system.

According to the Can Tho academics, rice accounts for over half of the carbon emissions from agriculture, contributing significantly to global warming.

If the industry can change its approach to rice production, not only will carbon emission levels be lower but also productivity can increase by up to 50% due to reduced requirements of fertilizers, pesticides and labor.

Chieu decided to join the project.

“It sounded good. At that time my profit was only around 30%.”

The 540 hectares of paddy fields belonging to members of the 7B Canal Cooperative in Phu Tan District in An Giang Province and Tan Hiep District in Kien Giang were among the first to undertake the low-emission rice production.

The project has been run by the Can Tho University’s Mekong Delta Development Research Institute since 2012, with funding from the Australian government.

Following the pilot project, the model was taken to various other locations for the next 10 years.

It was expanded into a large-scale sustainable development project with the aim of farming high-quality low-emission rice varieties on one million hectares, and received approval from the government at the end of 2023.

Benefits to farmers and environment

After signing up for the pilot project, Chieu tried to convince other people in the cooperative to join, but it was hard. The new model reduced seed density to just 120 kilograms per hectare, half the traditional level of 230 kg.

The approach to irrigation also changed from full water immersion to a mixture of immersion and dry layers of soil, which concerned many farmers.

Chieu recalls: “Farmers were concerned, and legitimately so. It is their whole livelihood; they cannot fail. I had to convince them repeatedly, and in the end they agreed.”

He organized many meetings to highlight the economic benefits of the new model. He tried to convince one person at a time. Some were not entirely convinced, but still decided to sign up.

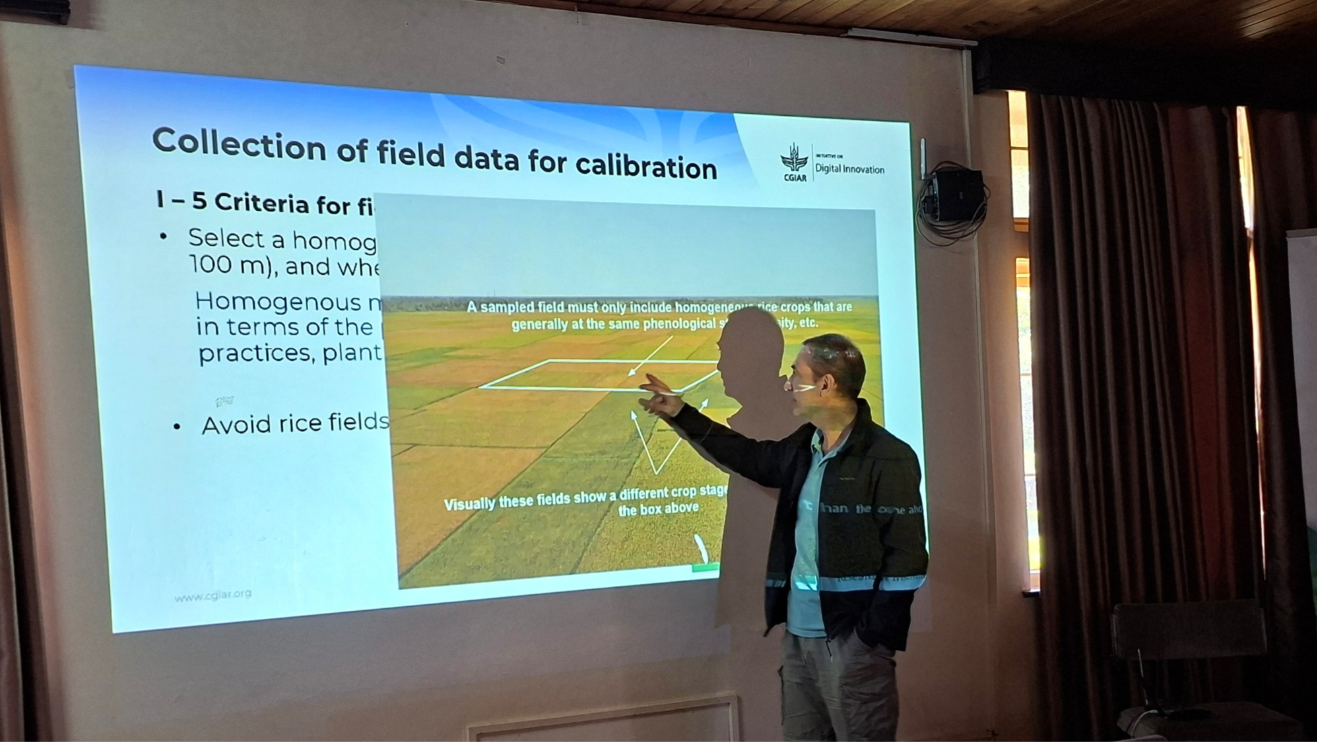

A plot was selected and half of it each was used to grow rice using the traditional and new methods. Based on instructions from experts from Can Tho University, the farmers followed certain approaches, using the designated varieties of rice, reducing water, fertilizer and pesticide use, aiming at reducing post-harvest loss of yields. All of this was meant to reduce the overall greenhouse gas emissions.

Associate professor Huynh Quang Tin of the Mekong Delta Development Research Institute explains that rice is one of the most significant sources of carbon emissions, mostly methane, in agriculture.

To reduce them, farmers need to switch from full water immersion to a mixture of immersion and dry periods, reducing the times of watering to five or six per crop, and the water should not rise beyond 3 cm.

The pilot winter-spring crop in the 2012-13 season was hit by unfavorable weather. Besides, farmers were not used to the new method and did not correctly follow the irrigation guidelines.

But the experts and agricultural officials were diligent in following up with them, and told them to keep detailed records of their farming procedures.

The farmers gradually got the hang of the method.

Chieu says: “Upon succeeding, farmers saw the benefits of the new method. Their rice also had less harmful substances. Gradually more people switched to the new agricultural method without the need for persuasion.”

The model has increased yields by 9% and incomes by 31%, while reducing emissions by 19-31%. Farmers’ profits are VND7.27 million (US$300) per hectare higher than from the traditional method.

“The success was way beyond what we expected,” Dr. Tin says.

Despite planting at a lower density, the new method produced similar panicles and seeds.

The mixed water irrigation approach kept the rice plants from falling and made it easier to harvest with machines, while also reducing the use of pesticides and chemicals.

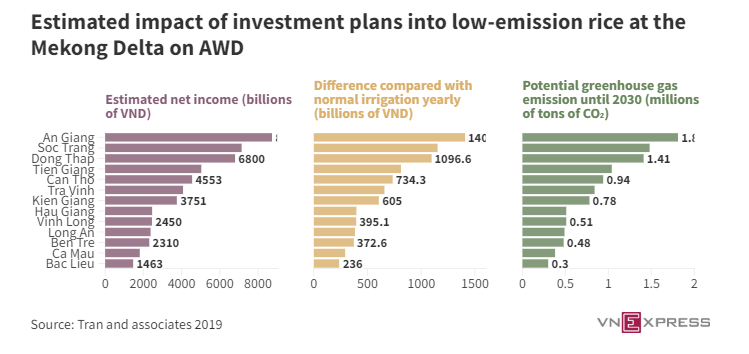

After the trial, scientists estimated that if the new method was implemented over 1.8 million hectares of rice fields in the Mekong Delta, the savings would be VND7.4 trillion and 2.4 billion cubic meters of water, and greenhouse gas emissions would be reduced by 13.86 million tons.

Dr. Tin says: “At that moment we also thought about selling carbon credits to help farmers improve incomes. Many markets are willing to buy carbon credits to protect the environment.”

However, at the time, the issue was not on the front burner. According to Dr. Tin, Vietnam did not have comprehensive policies yet for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and the measurement of greenhouse gases on a large scale was too costly.

The project remained on hold, he says.

“We were ahead of the time. Localities joined the program because it brought direct financial benefits to farmers. They did not really think about the environmental impacts.”

The project led to other localities in the delta following suit. In 2023 the one-million-hectare project was approved with a goal of reducing farmers’ costs by 20% and increasing profits by 50% by 2030.

This is expected to be an agricultural revolution for the Mekong Delta, creating a fundamental change in the sector from being quantity-focused to quality-focused.

Managing every step of rice production

In early July 2024 rice harvesters were working hard on the 50 ha of rice fields belonging to Thuan Tien Cooperative in Can Tho City.

It was the first season of a pilot program to grow high-quality and low-emission rice. Bedsides Can Tho, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development has also chosen the four provinces of Soc Trang, Tra Vinh, Dong Thap, and Kien Giang, all of which have alluvial and acid sulphate soil, for the pilot.

Through the season, farmers barely had to enter their paddy fields since everything from tilling the land and dispersing the seeds to fertilization and harvesting were done by machines.

Thuan Tien Cooperative’s director, Nguyen Cao Khai, said a rice harvester could harvest five to seven hectares of paddies a day, which is equivalent to the work done by 100 to 140 people.

A fertilization drone could cover up to 10 ha per hour as against two hectares per day by a human, he said.

“With advanced technologies and machineries, a farmer could manage 15-20 ha. A paddy field needs no physical work from humans any more.”

He said in the first season the cooperative reduced seed dispersion to just 60 kg per hectare, or 50% of the usual rate.

Farmers did not disperse the seeds by hand but used machines, and reduced the application of fertilizers from three or four times per season to just two, leading to a decrease of 20% in the total amount of fertilizers used.

The yield increased from 6.1 tons to 6.5 tons per hectare, and the rice plants no longer collapsed.

Production costs decreased, helping increase profits by VND6.2 million ($250) per hectare while also decreasing carbon emissions by 2-5 tons per hectare compared to the traditional method.

“If the initial 50 ha prove successful, we will switch to the new method on the remaining 512 ha to create a cooperative of low-emission rice production,” Khai says with great hope for the future.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development targets growing low-emission rice on 180,000 ha in 12 localities next year and issuing carbon credits.

By 2030 it plans to increase it to 820,000 ha.

One million hectares of low-emission rice fields could fetch carbon credits worth $100 million a year at an estimated $10 per credit. One carbon credit is equal to one metric ton of carbon dioxide, and Vietnam has signed a Letter of Intent with the Organization for Forest Financial Enhancement (EMERGENT), to sell carbon dioxide at the price of $10 per tonne.

Thirty six countries participate in the carbon credit market, which offers a big new opportunity for Vietnam.

Having participated in a similar model in four provinces in the Mekong Delta, Professor Nguyen Bao Ve, former head of the agriculture department at Can Tho University, says the low-emission rice production model helps mitigate problems like harsh natural conditions, decreased productivity, increased water and fertilizer use, and carbon emissions.

But experts say the model can only be successful on a large scale and with advance technologies, which requires large investments.

It is not suitable for small-scale farming, they warn.

Farmers need to be part of a cooperative and jointly adopt the new model.

Companies need to be in on the deal to ensure farmers can sell their produce at steady prices over the long run.

This was a big reason why a similar program in the Mekong Delta in 2011, with weak links between farmers and corporates, high risks and low profitability, did not attract investment.

“State-owned enterprises focused on government contracts, accounting for 53% of the exported rice, but did not care about quality, market expansion or branding,” Ve says.

He says corporates should be made to take responsibility for everything from production to distribution, while farmers only contribute lands like shareholders.

“The 1-million-hectare project’s success is the path for sustainable development, helping farmers change their lives.”

Nguyen Phuong Lam, director of the Can Tho branch of the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry, says companies mostly buy and export low-quality grains, and do not pay attention to improving added value for rice and lack specialized logistics, leading to high costs.

Now, 90% of the rice grown in the Mekong Delta has to be transported to HCMC or the southeast before being exported, leading to additional costs of $10-13 per ton, he points out.

If the Mekong Delta can export directly from local ports like Can Tho and Soc Trang, the profit margin will be considerably higher, he says.

“Logistics costs for rice exports are higher than for other commodities. To develop sustainably, we need to invest in specialized ports and logistics systems in the Mekong Delta.”

Protecting farmers’ livelihoods

Agricultural expert Professor Vo Tong Xuan, now deceased, said in an interview in July: “Rice farmers generally carry the responsibility of producing food for the whole nation. But their incomes are not as high as those who grow other crops.”

Therefore, most countries subsidized farmers to ensure their livelihoods, he said.

For instance, the EU provided its wheat farmers with $5,000 a year, and was considering raising the amount to offset rising costs, he said.

In Vietnam, rice farming localities received a subsidy of VND1 million ($40) per hectare per year, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development was proposing to double it, and triple it in areas where agriculture needed to be protected or new technologies were being trialed, he said.

If Vietnam wished to change from a quantitative-focused approach to a qualitative-based one, the agriculture sector needed to change fundamentally, he pointed out.

“The one-million-hectare project by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development is strongly showing this determination for change. But farmers also need to change their approaches to agriculture, from production to land preparation and environmental protection. It is the only way.”

Le Thanh Tung, deputy head of the ministry’s farming department, says the one-million-hectare project not only pays attention to infrastructure development but also restructures the entire rice production industry in the Mekong Delta.

The general goals are to reduce costs, increase the rice value, reduce emissions, and develop rural areas sustainably, he says.

The funding for the project will come from localities, the government, the International Rice Research Institute, and corporates, he says.

While the government will provide funds for the technology, localities will be responsible for providing infrastructure and other materials, he says.

The core team will comprise cooperatives, farmer organizations and corporates working closely together to ensure sustainable production and outcomes for rice production, he says.

“Farmers participating in the project will not have to pay anything for three seasons. We are doing all we can to support the farmers.”

After the first six seasons from 2012 to 2014 all members of the 7B Canal Cooperative in Kien Giang switched to low-emission rice.

“Even if you try to persuade them, no farmer will go back to the traditional method, because it is not profitable,” Chieu says, laughing.

The paddy fields of the 7B Canal Cooperative became the exemplar for cooperatives and experts.

The farmers who first adopted the model are glad to see it spread far and wide.

However, when asked about carbon credits, Chieu says farmers cannot really understand them very well.

After 12 years in low-emission rice production, he does not really know how many carbon credits the cooperative earned or how much money they are worth.

“Farmers hear that they can sell carbon credits, and only know that much. If a guideline is provided, they will follow. [But] they will only believe it when they receive the money.”

Story by Huy Phong, Ngoc Tai

Graphics by Khanh Hoang

https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/environment/rice-farmers-join-revolution-for-low-emissions-high-profits-4797481.htmlPublished Date: October 8, 2024