Tags

From China to India: Can perennial rice rewrite water use in agriculture?

Explore how perennial rice, with lower irrigation demands and deeper roots, could revolutionise water use in India’s climate-vulnerable farming systems.

India’s water crisis is inseparable from its rice fields. As the nation’s most water-intensive crop, rice consumes nearly a quarter of irrigation withdrawals, pushing groundwater reserves to alarming lows in states like Punjab, Haryana, and Tamil Nadu. With climate change driving erratic monsoons and rising temperatures, India’s dependence on conventional paddy farming is becoming increasingly unsustainable. Enter perennial rice—a scientific breakthrough that regrows season after season without replanting, drawing from deeper roots and demanding far less irrigation.

First developed in a quiet agricultural plot in Yunnan, China, this crop is now entering India through trials in Odisha and Tamil Nadu. Beyond yield and cost benefits, its promise lies in rewriting India’s water equation, offering a pathway to conserve groundwater, reduce methane emissions, and build resilience in smallholder systems. But can this innovation overcome ecological, policy, and farmer adoption hurdles to become a true game-changer for Indian agriculture?

A new study, ‘Perennial rice – An alternative to the ‘one-sow, one-harvest’ rice production: Benefits, challenges, and future prospects’ by researchers Vijayakumar Shanmugam et al., published in Farming System, lays out the promise of perennial rice for India. It dives into its genetic foundation, environmental implications, and on-ground performance, offering an in-depth review of how perennial rice could potentially shift the nation’s rice economy towards greater sustainability and resilience. But what makes perennial rice so radical?

What is perennial rice?

The study describes perennial rice as a cross between Oryza sativa (cultivated rice) and Oryza longistaminata (a wild, rhizomatous African species), bred primarily by scientists at the Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (YAAS). After years of molecular breeding and genetic selection, China released PR23 in 2018, which is a perennial rice variety that has since shown promising yield stability in various agroecological zones.

Unlike conventional rice, which needs to be replanted every season, perennial rice can regrow from the same root system for multiple years typically up to 5 seasons. Thanks to its rhizome-based regeneration, which means that once established, it doesn’t require tilling, sowing, or nursery preparation between cycles.

But India isn’t China. Our soils, rainfall patterns, and smallholder plots make adoption far more complex. Researchers caution that perennial rice here will need its own path, adapted varieties, farmer training, and collaborations with global institutions like International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and Consortium of International Agricultural Research Centers (CGIAR). Still, the question remains: can this water-saving crop be the next big leap for India’s thirsty rice fields?

Growing grain without draining groundwater

Ask any farmer in India what keeps them awake at night, and the answer often circles back to water. Rice, our staple grain, is also one of our thirstiest crops, demanding between 3,000 and 5,000 litres of water just to produce a single kilogram. Add to that the practice of puddling, where fields are deliberately flooded, and we’re not just feeding rice, we’re bleeding water. So much of it vanishes through evaporation and seepage, while the soil beneath is left degraded and gasping methane into the air.

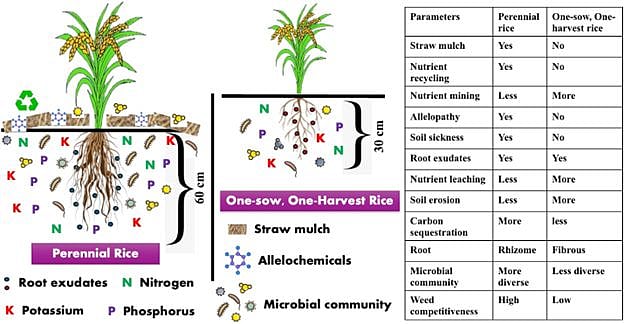

This is where perennial rice changes the story. Because it doesn’t need replanting every year, farmers avoid the most water-intensive steps—nursery raising, transplanting, and repeated flooding. Instead, its deep, established roots tap into subsoil moisture, needing less frequent and lighter irrigation. It’s not about drenching fields anymore; it’s about steady, efficient watering that keeps crops alive while protecting groundwater.

Early trials show the difference is dramatic—up to 30–40% less water use compared to conventional rice. For water-stressed states like Punjab, Haryana, and Tamil Nadu, where aquifers are sinking fast, that’s not just a statistic. It could mean the difference between survival and collapse for future rice cultivation.

Think of what happens when a paddy field is constantly flooded. The standing water doesn’t just vanish into thin air—it evaporates, it seeps away, it carries nutrients down with it. Farmers lose precious moisture, soil fertility takes a hit, and weeds find their chance to flourish. Perennial rice offers a way out of this cycle. With no puddling and less standing water on the surface, these fields hold on to their moisture instead of losing it. The result? Less evaporation, fewer waterlogged patches, and soils that can feed plants more efficiently.

And there’s another layer that contributes to climate resilience. With deeper roots and better moisture retention, perennial rice weathers erratic rains and short droughts far more gracefully than conventional rice. That’s crucial as India faces more unpredictable monsoons every year. No wonder researchers see a natural fit with national water programs like Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY) and Atal Bhujal Yojana. If perennial rice is integrated into such efforts, it won’t just save water—it could strengthen food security while building resilience into our farmlands.

Fig. Comparison of perennial rice and one-sow, one-harvest rice production system

Perennials as allies for water, biodiversity, and balance

Other than this, perennial rice has the potential to solve several entrenched problems of Indian agriculture like:

- Labour and cost savings: Paddy cultivation in India is extremely labour-intensive—especially during land preparation and transplanting. By eliminating the need to replant annually, perennial rice could reduce labour inputs by 50–60%, as well as cut costs for seeds, fuel, and irrigation. This is especially significant in eastern India, where outmigration has left behind labour-scarce rural areas.

- Soil health and carbon sequestration: Continuous tilling damages soil structure and accelerates organic carbon loss. With perennial root systems intact year-round, soil erosion is reduced, and organic matter builds up over time. Studies cited in the paper suggest increased microbial biomass and improved soil nutrient profiles in fields with perennial rice.

- Climate resilience: India’s climate variability that includes intense monsoon flooding, unseasonal droughts, and heatwaves is making annual cropping less predictable. The robust root systems of perennial rice improve water retention and allow plants to recover faster from stress events. With climate risks projected to increase, especially in states like Odisha, Assam, and Bihar, such resilience could be crucial.

- Biodiversity and agroecology: Perennial systems promote better ecosystem services—pollination, pest control, and biodiversity retention. Unlike monocultures that are cleared after harvest, perennial fields offer stable habitats for insects and birds. There’s also reduced herbicide and pesticide use due to lower weed pressure in undisturbed soils.

Deep roots for resilience in a changing climate

Field trials in China show perennial rice yields of 6.8–7.5 tons per hectare in the first year and 5.4–6.3 tons in subsequent years. While slightly lower than top-performing hybrids, the cumulative yield across years without the cost of replanting, makes it economically superior. In comparative cost-benefit assessments, perennial rice cultivation saves up to 40% in total input costs over a three-year cycle. These include savings on seeds, fuel, irrigation, and fertilizers.

While Indian trials are still in the early phase, pilot studies in Tamil Nadu and Odisha suggest similar trends. One farmer in Mayurbhanj who participated in an informal trial told researchers: “I could see the shoots come up even after I thought the crop was over. It was a surprise—and a relief, especially when my neighbour had to spend again on seeds after a flood.”

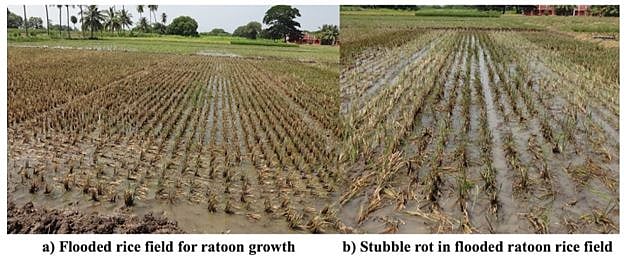

Fig: Rice field preparation for rice regrowth a) flooded field after rice crop harvest b) potential stubble rot issue.

Barriers and challenges

However, the perennial rice revolution is not without its complications.

- Genetic instability and yield decline: Over successive seasons, the yield of some perennial rice varieties tends to decline. This is often due to the degeneration of tillers, pest buildup, or nutrient depletion. Researchers are still working to breed more genetically stable and pest-resistant lines for Indian conditions.

- Disease and pest pressure: Continuous cropping can attract pests and diseases that would otherwise be broken by seasonal fallows. Integrated pest management strategies would need to be tightly woven into perennial systems.

- Seed market disruption: With fewer seed purchases each year, traditional seed markets—and their supply chains—could be disrupted. “Seed producers may see this as a threat,” the paper warns, suggesting the need for new institutional models to manage perennial seed certification and distribution.

- Farmer training and extension: Transitioning to perennial rice requires a shift in agronomic practices. Extension agencies will need to train farmers on pruning, nutrient cycling, pest surveillance, and water management in perennial systems.

- Policy support and incentives: Without institutional support, perennial rice may struggle to scale. Current input subsidies, crop insurance norms, and yield monitoring systems are tailored for annual crops. Policies must be adapted to accommodate perennial timelines and performance metrics.

Global context and India’s role

The push for perennial grains has gathered momentum globally. In the U.S., The Land Institute has developed Kernza (a perennial wheat). In Africa, trials on perennial sorghum are underway. China has already brought over 15,000 hectares under perennial rice, with plans to scale up. For India, this could be a pivotal moment to lead South Asia in perennial grain research. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), the Central Rice Research Institute (CRRI), and state agriculture universities are ideally positioned to pilot region-specific trials and breeding programs.

A path forward

Perennial rice is not a silver bullet, but it could be a powerful piece of the sustainable agriculture puzzle. The authors advocate for a phased rollout:

- Short term (0–3 years): Launch region-specific trials in five agro-climatic zones; initiate awareness campaigns and farmer field schools.

- Medium term (3–5 years): Develop genetically stable and pest-resistant Indian cultivars; create pilot models for input savings and market linkages.

- Long term (5–10 years): Integrate perennial rice into climate-resilient agriculture schemes, including PM-KUSUM and National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture.

At its core, the idea is to shift from extractive to regenerative agriculture. As the paper notes, “Perennial rice is not just a crop, it’s a philosophy of farming that aligns with how nature actually works.”

Perennial rice represents a powerful opportunity for India to rethink how food and water systems intersect. By cutting irrigation demand, reducing labour dependence, and enhancing resilience to climate extremes, it addresses some of the deepest cracks in India’s agricultural model. Yet, its future hinges on more than agronomy.

Farmer acceptance, supportive policies, and inclusive research will determine whether perennial rice can scale. Integrating it into national water conservation programs, crop insurance frameworks, and state-level extension systems could transform it from a scientific curiosity into a cornerstone of climate-smart agriculture. If nurtured carefully, perennial rice may do more than yield grain; it could restore balance between farming and water, ensuring India’s fields thrive without draining its aquifers.

Vijayakumar Shanmugam, Vikas C. Tyagi, Gobinath Rajendran, Suvarna Rani Chimmili, Arun Kumar Swarnaraj, Mariadoss Arulanandam, Virender Kumar, Panneerselvam Peramaiyan, Varunseelan Murugaiyan, Raman Meenakshi Sundaram, Perennial rice – An alternative to the ‘one-sow, one-harvest’ rice production: Benefits, challenges, and future prospects, Farming System, Volume 3, Issue 2, 2025, 100137, ISSN 2949-9119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.farsys.2025.100137.

https://www.indiawaterportal.org/agriculture/from-china-to-india-can-perennial-rice-rewrite-water-use-in-agriculturePublished Date: September 5, 2025