Tags

Attaining rice self sufficiency in Kenya – Komboka vs Pishori

By Kilimo News.

By Kimuri Mwangi

Data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) indicate that Kenya’s annual rice consumption is over one million metric tonnes, significantly exceeding the country’s production capacity of approximately 230,000 metric tonnes. This is an indicator that the country imports about 80 per cent of its rice.

The huge demand has been attributed to the popularity that the grain has gained, especially among young people who prefer rice over the number one staple food in Kenya, ugali made from maize flour.

Deliberate efforts are being made to make Kenya self-sufficient in rice, and the best lesson probably can come from our neighbours, Tanzania, who were in the same position some time back.

Tanzania has achieved rice self-sufficiency and is now exporting surplus to neighbouring countries. The country increased rice production under its first National Rice Development Strategy (NRDS-I). Tanzania’s National Rice Development Strategy (NRDS-II) aims to sustain national self-sufficiency and contribute to regional self-sufficiency.

Kilimo Trust, a not-for-profit organization working on agriculture for development across the East African Community in Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda, had a role to play in the Tanzanian rice self-sufficiency journey and is also replicating the same in Kenya.

I had the opportunity to engage Dr. Birungi Korutaro, the Kilimo Trust CEO, and Anthony Mugambi, the Kilimo Trust Team Leader in Kenya, on what Tanzania did to become a rice self-sufficient country.

Tell us how you have been involved in the rice value chain, and what lessons Kenya can learn to become self-sufficient in rice

Anthony Mugambi, the Kilimo Trust Team Leader in Kenya:

We have had interventions as Kilimo Trust in Tanzania on rice since 2011. I’ve worked in Mbeya, one of the largest rice-producing zones in Tanzania, since 2012. I’ve done bean and rice programmes there.

When the history of how Tanzania became self-sufficient in rice is written, Kilimo Trust, I think, will have a chapter in that book. Because through one of our flagship projects called the Competitive African Rice Initiative, funded by GIZ and other partners, which is one of the game changers in Tanzania, we came in, and I will relate that also with Kenya and what we’ve done as well on that.

In Kenya, we have the pishori rice variety from Mwea, which costs KSh 260 per kilogram of pure rice. I’m telling you, most of us, including myself, cannot sustain using it in our homes. Maybe, if my CEO comes visiting, she can have a bit of that pishori cooked for her because it is expensive.

But do you know why it is so expensive? Because it is very difficult to produce. If pure pishori is being cooked even a few blocks away, we can still smell it if it is pure pishori. But producing that rice costs a lot in terms of inputs because it is highly susceptible to diseases and is also a heavy feeder.

Tanzania had an equivalent of pishori—a high-aromatic rice called Kyela rice—and you will also hear about Mbeya rice when you go to Dar es Salaam. Very high aromatic. But unfortunately, it is a low-yielding variety. What you get per hectare or unit area is so low compared to non-aromatic rice.

When you go to what we call bitter cassava for processing, for instance, their yields are so high. But sweet cassava, which you can just peel and eat, has yields that are very low, and the same case applies to rice.

So, Tanzania had that rice which they had stuck to for years. Production was very low, the cost of production was very high, therefore completely uncompetitive.

So, what did we do? We went and found a variety of rice that was not necessarily very aromatic.

To understand why we are talking about semi-aromatic—in Nairobi, what passes as pure pishori rice is a very small percentage of pishori rice. The rest is imported rice that passes as pishori from Mwea. So, the population is consuming semi-aromatic rice blended with pishori.

So, in Tanzania, we realised that breeders had already come up with a semi-aromatic rice which was not non-aromatic but also not so aromatic. It is somewhere in the middle. But the yields are 2.5 times more than aromatic rice.

Therefore, if we are consuming more semi-aromatic rice in the market, why don’t we just produce semi-aromatic rice once and for all? We have done several market studies on several value chains across the region, not just in Kenya and Tanzania, one of them being rice. And we know the consumption patterns, we know the market segmentation, we know the preferences, we know who consumes what, we know how sensitive consumers are about the price. So, the issue of saying people love aromatic rice and consume aromatic rice is a fallacy.

In Mwea, over 99% of those farmers who produce pishori rice don’t consume it. They sell 100% of what they produce and buy imported rice for their households since they cannot afford their own rice.

In Tanzania, we introduced the semi-aromatic variety of rice called SARO 5, and we worked with the private sector, supporting them to invest in seed multiplication. Then, supporting farmers downstream to demonstrate to them and work with them. We put up an acre in a strategic place in the rural areas where we planted with them, did everything with them until harvesting, and milled with them.

The millers also saw that it can be milled, and the recovery rate (what you get if you put 10 kgs or 100 kgs of your rice) is a very good percentage of rice, with fewer breakages. So, we took the value chain actors through that process so that they appreciate it, then they adopt it. Therefore, most of the farmers moved away from that very high-aromatic rice to that semi-aromatic rice.

That means 2.5 times more yields, 2.5 times more income, and more volumes also for them. We also worked with the seed producers, seed companies, and farmers who are doing production. The millers were also adopting this rice so that they are able to expand their capacity.

Fortunately, in our programme, we had a grant component where we were able to give them a grant. Some of them got about KSh 50 million, and they were able to invest in the extension system, staff, and farmer outreach.

With that kind of money in the bank, those companies became attractive to financial institutions, and they were able to expand even in areas where we were not intervening.

Now, the same case has happened in Kenya.

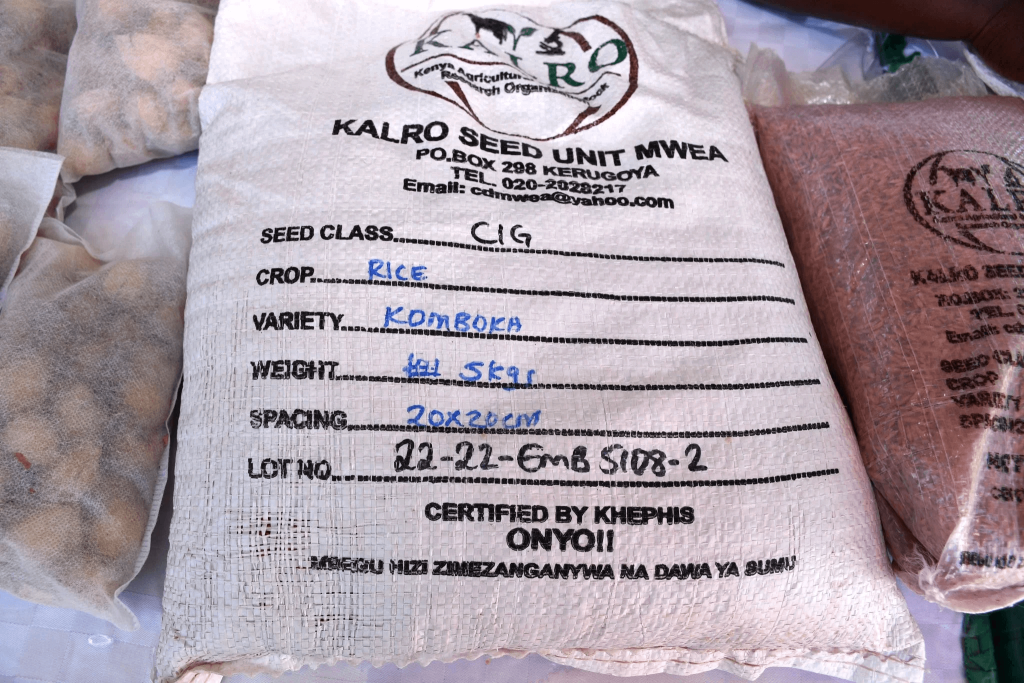

You may have heard about the story of Komboka rice. Komboka rice is the equivalent of SARO 5 here in Kenya. We picked that up when we brought CARI East Africa (Competitive African Rice Initiative) here in Kenya.

The variety had been developed by IRRI (International Rice Research Institute) for many years; it was actually in the lab, but there was no uptake. We therefore used the same strategy we used in Tanzania by involving all stakeholders. We let the farmers and the other value chain actors select a variety of rice for themselves, based on the consumer and plant together. We cook all the varieties, and each one tastes, and we note which tastes better and yields more. Then the miller says the one with a better recovery rate.

We actually go out there in the field, with the researchers, with government officials, consumers and everyone represented, and then we select a variety. We go out there full throttle, basically championing it amongst farmers, amongst millers, and the uptake becomes much easier because they chose it for themselves. We didn’t come and tell them, “Guys, here’s a variety that does very well,” while they have not even seen it doing very well.

Komboka today is a success story. Kilimo Trust, in collaboration with other organizations like KALRO and IRRI, has been involved in promoting and supporting the adoption of Komboka rice to increase rice production and reduce reliance on imports in East Africa, also incorporating the rice promotion programme at the Ministry of Agriculture.

Komboka is in Tana River, Kwale, Taita Taveta, and Western Kenya. Today, we’ve started exporting Komboka rice to Rwanda because it has become so successful.

We also invested again in seed multipliers, certifying seed merchants to be able to ensure that the seed is within the areas where it can be found.

Dr. Birungi Korutaro, the Kilimo Trust CEO:

What we did in Tanzania was just to emphasise to all the actors in the value chain, right from the input, seed, providing high-yielding varieties, production, and good agronomic practices, to ensure that SARO 5 gives you five, six, or eight metric tonnes per hectare.

We showed them how to reduce the losses, including how to dry it so that they reduce breakage. So, competitiveness has to be addressed along the entire value chain in terms of increasing efficiency. But we also found that, other than at the farm level, to make Tanzania more competitive, we needed to work with the government.

We were also able to do policy studies and show the government that the ad hoc export bans that they were imposing on rice were not only increasing the cost of rice in Tanzania and making it less competitive, but the farmers were also losing even more with the export bans. So, as they were thinking that they were keeping the rice in Tanzania, it was not better for Tanzania because the farmers were losing. We were able to show them that evidence.

And so that’s why you now see that from 2015, 2016, the export bans reduced when they understood the impact of some of those things. We have seen that whether it is in Uganda or Rwanda, transformation in the agriculture sector is a public-private collaboration.

That transformation in Tanzania was also heavy on the private sector, as they also invested. Private companies have square miles of irrigation schemes. They have gotten tax exemptions to import levelling machines and all that, but it was a collaboration.

Published Date: May 19, 2025