Weekly Rice Market

(Indicative Quotes)

Basmati Rice

Basmati Rice | Indicative Quotes | Updated Weekly

Global Market | White Rice

White Rice | Indicative Quotes | Updated Weekly

News

Iranian firm issue...

Monitoring Desk Iranian company Jahad Sabz has issued an international tender to procure 10,000 metric tonnes of rice from Pakistan, according to a tender document circulated to

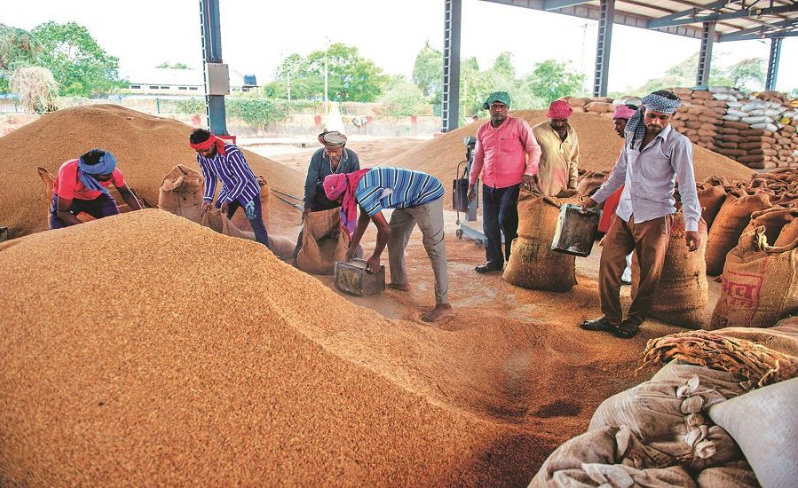

Wholesale rice pri...

Shahadat Hossain Farmers say they are struggling to secure fair prices for paddy despite persistently high rice prices. Highlights: Wholesale prices of coarse and medium-grade

Myanmar to export ...

Global New Light of Myanmar The Myanmar Rice Producers and Planters Association stated that Myanmar and EU trade partners have agreed shipment of Myanmar’s parboiled rice (6.22

Philippines to sca...

The Philippines is expected to reduce rice imports in 2026 to below 4 million tonnes (mnt) as domestic palay (unmilled rice) production rebounds from weather-related setbacks,

Japan hikes intere...

By AFP The Bank of Japan hiked interest rates to a 30-year high of 0.75 percent on Friday, the first increase since January, as it said the economy had shown signs of improvement.

Latin American Mar...

NEW ORLEANS, LA – The 6th U.S. Rice Quality Symposium, a key part of the annual USA Rice Outlook Conference, was held here last week helping to ensure U.S. rice stays

Govt revises rice ...

NEW DELHI: The Central government on Friday reduced the price of rice supplied from its buffer stock to grain-based ethanol producers by a significant 20 per cent, within 10 days

Tariff on rice no...

Ada Pelonia BROAD agriculture sector coalition Sinag has renewed calls to reinstate the 35-percent tariffs levied on rice imports as retail prices remain elevated. The group made

GI certification l...

By Pattaya Mail BANGKOK, Thailand – The Department of Intellectual Property (DIP) reports that Geographical Indications (GI) have increased the economic value of Thai rice

Featured Registered Companies

RNT Tube

What Trump’s Tariffs On Basmati Rice Means For India? Experts Answer

December 12, 2025

Statistics

Sustainable Rice

Farmers Place

Upcoming Events

Forex Rates

Open Market Forex Rates

Updated at:

From | ||

|---|---|---|

To | ||

| Countries | Currency | Spot Rate |

Enjoyed the read?

Join our monthly newsletter for helpful tips on how to run your business smoothly