Tags

The Paddy Price Trap: Why Sindh’s Farmers Lose In A Market Without Rules

While Pakistan earns $3.2 billion from rice exports, the farmers who grow it receive barely half the price they did a few seasons ago, leading to widespread anger.

Iftikhar Talpur

October marks the start of Sindh’s paddy-harvesting season, from the lush lowlands of lower Sindh to the upper reaches of the province. Yet what should be a time of reward has again turned into a season of protest. This October, growers across paddy extensive areas in lower Sindh blocked highways and staged sit-ins outside rice mills and deputy commissioners’ offices.

Their grievances were familiar: unjustified deductions for “moisture content” and faulty weighing scales that record 32–35 kilograms as one maund instead of 40 depriving farmers of up to eight kilograms on every maund. Over a harvest, this silent manipulation translates into enormous collective losses, while millers quietly pocket the difference. The injustice is compounded by a sharp fall in market prices from around Rs 3,400 to barely Rs 2,000–2,200 per maund.

These demonstrations mirror previous years and continue to go largely unnoticed by those responsible for market regulation. The Sindh Abadgar Board and other associations have repeatedly sought oversight, but the agriculture department remains silent. What began as sporadic outrage has hardened into a grim harvest ritual one in which protest banners appear before the government ever does.

For Sindh’s rice farmers, a bumper crop can be a curse. They face rigged scales, arbitrary deductions, and a price crash that makes cultivation unviable

The story is neither new nor confined to rice. Sugarcane growers faced similar neglect until many abandoned the crop. Cotton farmers, too, saw margins vanish amid arbitrary grading and price manipulation. Smallholders, unable to absorb soaring input costs, quietly shifted to other crops or tenancy arrangements. The question remains: why do these cycles persist, and who is accountable?

This crisis persists despite record cultivation. In 2025, Sindh’s rice area expanded to 2.1 million acres (851,300 ha) exceeding the provincial target with the southern districts forming the heart of production. Yet the rewards of a bumper crop still bypass those who grow it. In Badin, farmers describe hauling hundreds of maunds to mills, only to be told their grain is “wet” or “light.” The same pattern repeats in Sujawal and Thatta. No government department inspects or certifies these scales.

According to trade directories, Sindh hosts about 293 rice mills, mostly privately owned. They dominate both domestic procurement and export supply chains, deciding what growers are paid and when. The lack of oversight from the Weights and Measures Department, Agriculture Extension, or the Sindh Food Authority enables these practices to persist unchecked.

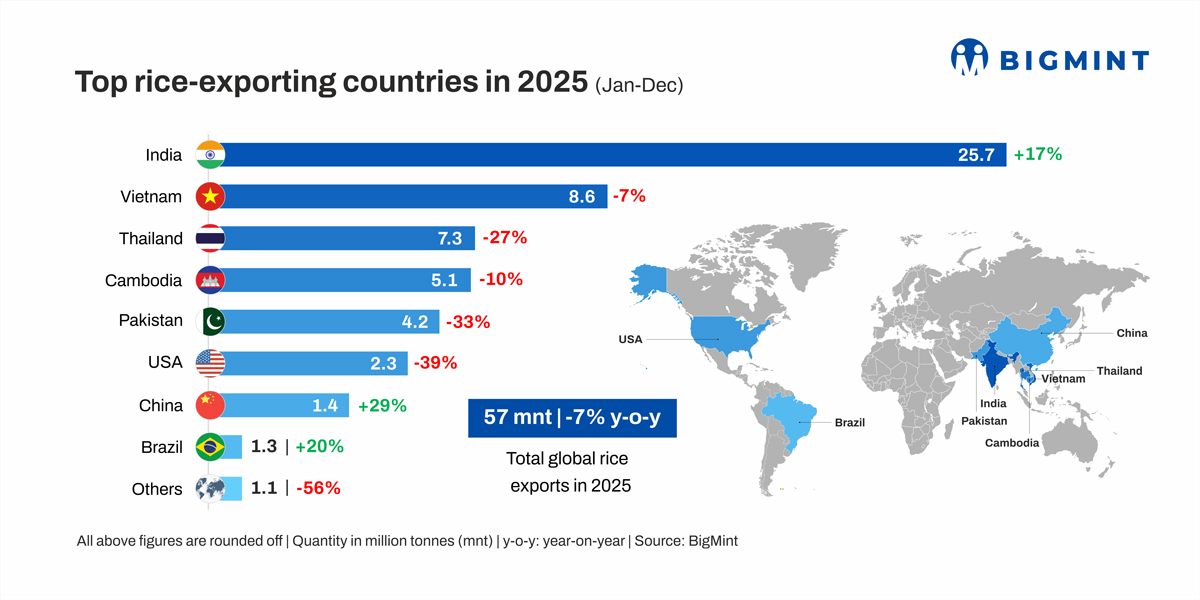

Meanwhile, rice remains one of Pakistan’s leading export earners. In the first eleven months of FY 2024–25, the country exported 5.54 million tons of rice worth US $ 3.2 billion. Yet the prosperity reflected in export figures conceals a painful paradox: as global demand rises, farm-gate prices in Sindh fall.

Growers in Lower Sindh now receive between Rs 2,000 and Rs 2,200 per maund (Rs 52–55/kg), compared to Rs 3,600 just a few seasons ago. By contrast, in 2024–25 the export-equivalent price for long-grain rice averaged Rs 6,520 per maund, while premium Basmati fetched Rs 12,720 per maund abroad. For millers, by-products like husk, bran, and broken rice further boost profit. For farmers, the numbers barely break even. The result is a steady transfer of wealth from producers to processors.

The recurring crises in rice, sugarcane, and cotton expose a deeper structural flaw: the collapse of agricultural market governance. The provincial agriculture department, tasked with protecting growers, has retreated from its regulatory role. There is no standardized moisture-testing protocol, no certified scale inspection, and no official price notification. The Competition Commission of Pakistan remains passive against miller cartels, while farmer cooperatives are too weak to challenge them.

This vacuum lets mill owners, traders, and politically connected landlords dictate terms, while small and tenant farmers have no recourse. The government’s reluctance to intervene perhaps out of fear of market backlash has effectively institutionalised exploitation. Sindh’s agricultural markets today are vibrant in production but lawless in transaction.

For smallholders, the arithmetic no longer works. Rising diesel, fertiliser, seed, and labour costs erode margins even before deductions at the mill gate. Many families depend on informal credit, repaying debts with their harvests. When the final payment falls short, debt simply rolls over to the next season. The more water they pump, the more grain they grow yet the poorer they become. In parts of Badin and Thatta, younger farmers are already shifting to less water-intensive crops or urban wage work. What was once a reliable livelihood has become a yearly gamble.

These October protests are not mere local disturbances; they are symptoms of collapsing trust between growers and the state. If Sindh can set indicative prices for sugarcane and enforce procurement for wheat, there is no reason paddy should remain unregulated.

To begin restoring fairness, the government must standardise and certify all moisture meters and weighing scales, with annual inspections by the Weights and Measures Department. It should publish weekly indicative paddy prices through district agriculture offices and digitise receipts and moisture readings to prevent tampering. Farmer cooperatives must be supported to strengthen collective bargaining, while the Competition Commission should investigate miller collusion and impose penalties where exploitation occurs.

Beyond these administrative fixes, Sindh should establish a District Rice Price & Quality Committee in every major producing district. Chaired by the Deputy Commissioner, it should include representatives of growers, millers, and officials from Agriculture Extension, Price Control, Weights & Measures, Sindh Food Authority, and the Competition Commission, with input from the Sindh Chamber of Agriculture, Abadgar Board, and district irrigation officers. Meeting before each harvest, such committees could set indicative prices, define quality standards, and monitor procurement practices. Their decisions should be publicly announced and reviewed mid-season to resolve disputes.

Until these reforms take root, Sindh’s farmers will continue to gather on roads and outside mills each October a ritual of despair in what should be a season of abundance. The strength of a farming nation is not measured by its export figures but by the fairness of the field where its farmers stand. Until Sindh’s growers are given justice at the weighing scale and respect in the marketplace, every grain of rice they produce will carry the weight of neglect rather than the pride of harvest.

https://www.thefridaytimes.com/17-Oct-2025/paddy-price-trap-sindh-s-farmers-lose-market-without-rulesPublished Date: October 18, 2025