Tags

Is India’s CRISPR feat with rice a costly proposition?

ICAR has developed genome-edited varieties of rice, but has used patented CRISPR technology that will entail huge costs.

Latha Jishnu

For an organisation whose glory days are long past, new technology has helped the Indian Council of Agriculture (ICAR) find a place in the sun once again. In early May, ICAR, a vast organisation that employs several thousand scientists, announced that it had developed India’s first genome-edited (GE) rice varieties. All to the good, the two new rice varieties were tailored to meet the test of climate change by being drought-tolerant, faster-maturing and water-saving crops that required less nitrogen. Indeed, a historic milestone that “reflects India’s progress in cutting-edge biotechnology for sustainable agriculture and farmer welfare.” Such a pity that we have to burst this bubble; but burst it we must, since all these claims of ICAR stem from the use of borrowed technology— technology that is patented. This is problematic.

DRR Dhan 100 (Kamala) and Pusa DST Rice 1, the GE versions of already well-performing varieties, were developed by scientists at the Indian Institute of Rice Research, Hyderabad, and the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Pusa, using CRISPR-Cas technology. CRISPR, the acronym for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats”, is a technology that scientists use to selectively modify the DNA of living organisms. It acts as molecular scissors that can precisely cut a target DNA sequence, directed by a customisable guide. The most foundational of these technologies, CRISPR-Cas9, was discovered by Nobel Prize winners Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier in 2012. It uses a guide RNA to target the desired DNA sequence and the Cas9 enzyme as molecular scissors. Charpentier’s firm ERS Genomics, based in Dublin, is the global CRISPR Cas9 licensing leader and was awarded a patent in India in May 2022. It is this tool ICAR institutes have used in their GE rice breakthrough.

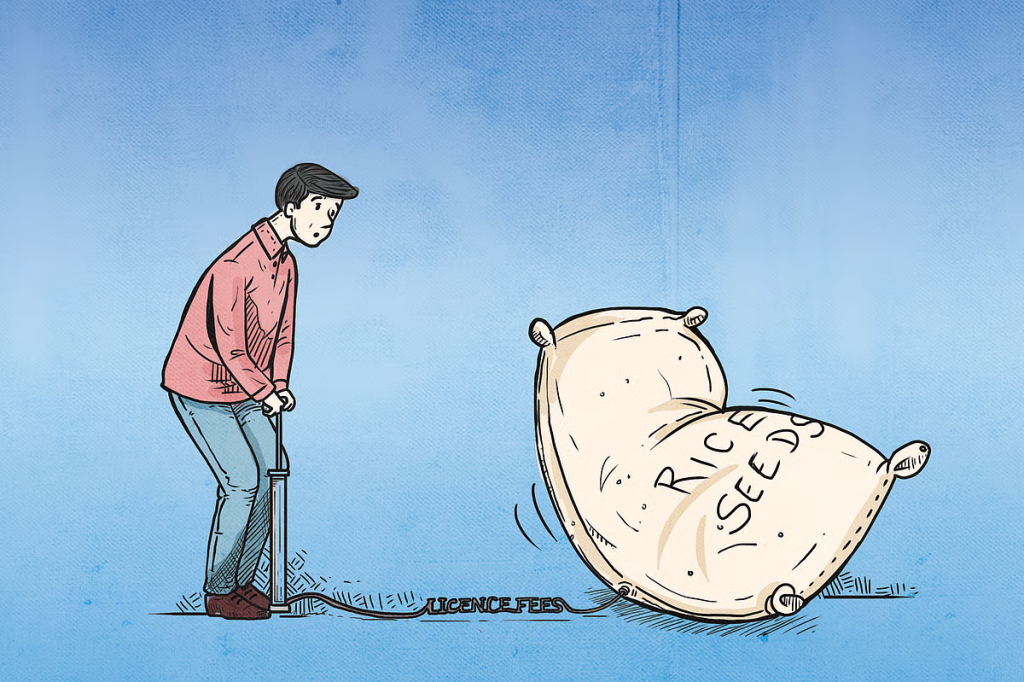

While the use of CRISPR-Cas technologies is permitted for academic research, patent-holders set the licensing rules and claim rights over discoveries made with their technology. This means commercialisation of any breakthroughs cannot be made unless legally licensed, and the licensing fees can be astronomical in some cases. It is strange that ICAR was not aware of the terms and conditions of using this patented technology. Initially, it waved off such concerns with a somewhat dismissive statement that the issue of intellectual property rights (IPRs) on the CRISPR-Cas9 technology would be resolved in due course. However, in a more recent interview, ICAR Director General M L Jat indicated that the organisation is now waking up to the problem it faces, though belatedly. He says the government will soon be buying the licence and that a high-level committee has been set up to negotiate the terms for commercialising the rice varieties.

Anurag Chaurasia, a scientist at the Indian Institute of Vegetable Research, which is part of ICAR’s huge network, warns that government research laboratories are “underestimating the importance of the patent and licensing rules that surround tools such as CRISPR.” He advocates a “one nation, one licence” policy for CRISPR toolkits that would allow researchers and institutions in India to access gene-editing technologies through a single government-negotiated agreement to reduce costs and simplify access. That may not be easy. CRISPR technologies are vast and complex. For one, ERS Genomics is not the only licensing company for CRISPR technologies, nor are Doudna and Charpentier the only patent-holders. A bitter battle about who actually discovered the technology is yet to be decided by the US courts after more than a decade of suits and counter-suits that called into question who the original innovators were.

The face-off in the US is between the Broad Institute of Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, on who was the first to conceive of using a CRISPR-Cas9 system to edit eukaryotic cells. Ranged against Broad is CVC (California-Vienna-Charpentier group) that comprises Charpentier and the Universities of Vienna and California. Both sides and their licensing companies hold a vast number of patents that cover several thousand applications, not all of which are affected by the ongoing patent battle.

ICAR’s GE varieties contain no foreign DNA and are comparable to conventionally bred types. They are exempt from strict biosafety rules under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, and cleared under India’s simplified regulatory framework for genome-edited crops. Cultivating them across 5 million hectares could yield 4.5 million additional tonnes of paddy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20 per cent (32,000 tonnes), promoting climate resilient farming.

The reason ICAR is focusing on GE crops is because in 2022, the government exempted the gene-editing technology based on SDN-1 (Site-Directed Nucleases, type 1) and SDN-2 techniques from the strict biosafety rules that govern GM or genetically modified crops under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. The logic it used was that GE, unlike GM, did not involve the insertion of any foreign DNA into any crop. Accordingly, ICAR was allocated Rs 500 crore for GE research and breeding in a variety of staple food crops, marking a strategic shift in policy. However, the Narendra Modi regime appears to have overlooked the licensing problem, just like the Manmohan Singh government did with Monsanto and its genetically modified Bt cotton. Monsanto earned humongous amounts from the licensing fees it charged Indian companies using its technology, and from farmers, who were charged trait fees on every Bt cotton seed packet they bought. One estimate put such earnings of the infamous company, now defunct and part of Bayer, at Rs 1,500 crore in the first seven years of its operations in India. Monsanto is what comes to mind as GE crops take centre-stage.

India then had no technology of its own and all of its research was based on the Monsanto Bt (Cry1Ac) protein, which meant that it could not proceed commercially. This time around, India is still deficient in technology, barring a breakthrough by a Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) institute. CSIR’s Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology has developed an enhanced genome-editing system that is useful in the medical field. But in agriculture we are zilch, while several countries, notably China, have made stupendous progress in GE. This is a telling reflection of India’s scientific prowess and its ability to keep up with laser speed of technological change. The sense of déjà vu is depressing.

There are other reminders of the time when GM cotton entered India in 2002, and more so when Monsanto tried to introduce Bt brinjal. The Coalition for a GM-Free India, which was in the vanguard of opposition to GM food crops, has termed the ICAR move to release GE rice—this would be three to four years from now—as “illegal, unscientific and irresponsible”. Does this ring a bell?

Published Date: May 24, 2025