Tags

How growing rice differently could ease climate change

Waterlogged paddy fields produce a lot of methane, but alternative techniques exist.

Susannah Savage

Rice is perhaps the world’s most important foodstuff — it feeds more than half the global population. But it is also one of the most climate-damaging crops.

Rice is usually grown in waterlogged paddy fields, which creates oxygen-starved soils that release methane — a greenhouse gas that is far more potent than carbon dioxide.

Techniques and technologies exist to change this, if farmers and governments can work together. “The deployment, the adoption, the government support . . . those are the factors that need to come together.” says Shalabh Dixit, a plant breeder at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI).

How does it work?

Methane from rice comes largely from the way it is grown — flooding paddy fields cuts off oxygen from the soil, creating the anaerobic conditions in which microbes thrive and release methane. The longer a field is submerged, the more methane builds up.

One technique, alternate wetting and drying, tries to break that cycle. The water level is allowed to drop 15cm below ground level before it is topped up, measured using a perforated tube inserted into the field. Allowing the soil to dry periodically reintroduces oxygen, disrupting the methane-producing microbes. This can reduce water use by about a third and lower methane emissions by 30-70 per cent without significant losses in the rice yielded, according to IRRI researchers.

Direct-seeded rice tackles the problem differently. Instead of raising seedlings in nurseries and transplanting them into flooded fields, farmers drill seeds straight into moist soil. Because the land does not need to be puddled and submerged for weeks, anaerobic conditions develop less often, and emissions fall.

Breeding varieties of rice that grow quicker also helps — reducing crop length by 30 days can cut methane output by a fifth.

What are the pros and cons?

As well as cutting methane emissions, farmers who switch to direct seeding save money on labour and diesel for pumping water. More judicious use of irrigation can also improve resilience in water-stressed parts of the world. Shorter-duration varieties mean farmers can harvest before late-season droughts or saltier soils set in. Together, these changes could make rice production more resilient as monsoon patterns shift.

But there are drawbacks. Flooding helps keep weeds at bay, so farmers switching to new methods often face higher costs for herbicides, crop rotations or new equipment.

They also need rice varieties that can handle these conditions, says Dixit at the IRRI. “The job that I have is to make sure that the varieties that are produced are adapted to this [new] system, and that they are able to handle all these changes, because the currently available varieties that we have for transplanted systems, they can’t handle that.”

Traditional varieties of rice often fail to germinate properly if fields are not flooded, he says. Access to these improved seeds and machines is still limited in many poorer regions.

Adoption itself is another hurdle. In the Indian state of Punjab, subsidies for drills and cash payments per acre have not fully overcome farmer worries about patchy germination or lower yields. Carbon markets, once seen as a way to reward low-emission practices, have also proved unreliable. Several early rice-methane projects were struck off by regulators, and new standards demand stricter monitoring, making it harder to promise farmers a steady income from the carbon schemes.

Will it help save the planet?

Scientists estimate that if alternate wetting and drying, or direct seeding were adopted across Asia’s paddies, tens of millions of tonnes of methane emissions could be cut each year. Because methane is far more potent than carbon dioxide but lingers in the atmosphere for only about a decade, the climate benefits would arrive quickly.

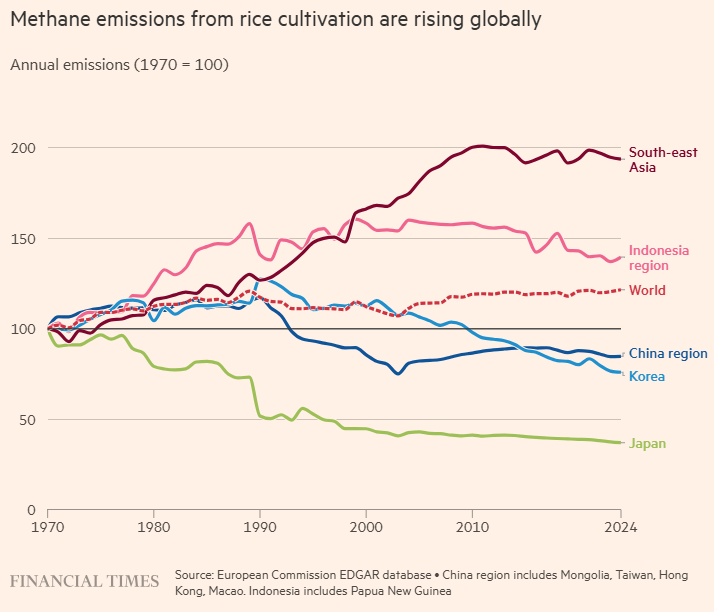

Methane is responsible for about a third of the rise in global temperatures, according to the International Energy Agency, and rice accounts for 10-12 per cent of global methane emissions.

The question is whether these methods can spread quickly enough. Irrigation schedules are often dictated by local water authorities, not individual farmers. Direct seeding requires new drills, crop varieties and weed control techniques. Many smallholder farmers are reluctant to change long-established practices unless offered clear incentives. Certification schemes such as the Sustainable Rice Platform are trialling premiums for “climate-friendly rice”, and some governments are exploring links to carbon markets, but for now progress remains patchy.

Has it arrived yet?

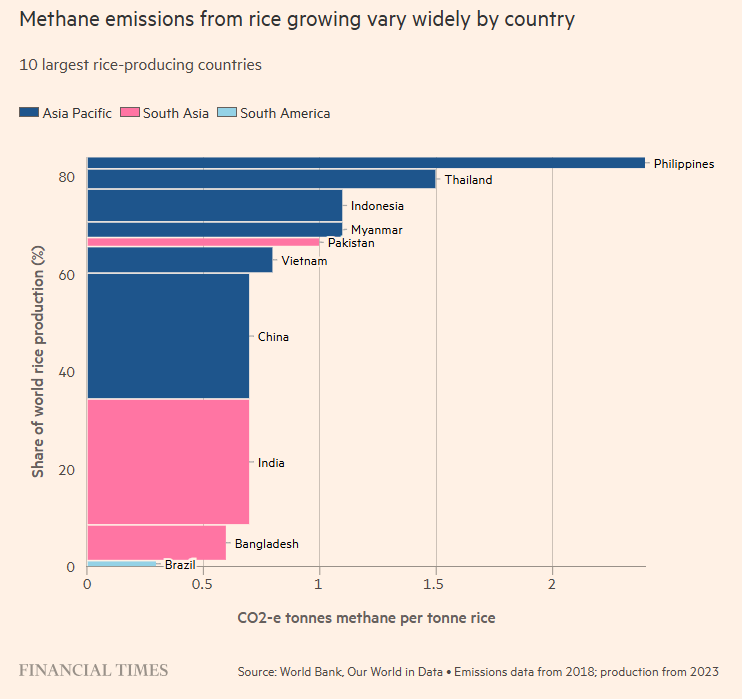

The farming methods themselves are not new — about 30 per cent of the world’s rice is already direct-seeded, in the US, Australia, Latin America and parts of Africa, according to IRRI. What is new is the push to expand this in Asia, where about 90 per cent of the world’s rice is grown.

Vietnam has pledged to make 1mn hectares of Mekong Delta rice “low-emission” by 2030, with backing from the World Bank and others.

But farmers often worry about weeds or poor germination, and in some areas irrigation rules still favour traditional flooding.

Carbon markets may provide another spur. In early 2025, Verra — the world’s largest carbon crediting body — launched a new methodology for rice methane projects, and the first Vietnamese project using alternate wetting and drying has already been listed. For now, though, most Asian paddies look much as they did a generation ago.

Who are the winners and losers?

If low-emission rice practices spread, the gains would extend well beyond climate targets. Consumers could benefit from cheaper production in water-stressed regions, while exporters such as Vietnam see an opportunity to brand themselves as suppliers of “sustainable rice” to premium markets. Seed companies and equipment makers also stand to profit from demand for varieties cultivated to be quicker-growing and for direct-seeding drills.

The adjustment will not be painless. Farmers tied to traditional flooding systems face steeper weed-control costs and higher risks if germination fails. Many smallholders lack the cash to invest in new machinery or herbicides, and adoption is often slow even when subsidies are offered.

There will also be knock-on effects in global trade. India dominates rice exports, and shifts in its production practices — or resistance to them — ripple quickly through world markets.

Who is investing?

Funding for low-emission rice is still a fraction of what is needed. Less than 1 per cent of the $13.5bn spent globally in 2023 on methane reduction went to rice, even though the crop accounts for a tenth of emissions, according to Alisher Mirzabaev, a scientist for policy analysis and climate change at IRRI. “Rice should be getting 20 times more than what it does now,” he says.

That gap matters because plant breeding and agronomic research are long-term projects. Breeding rice varieties suited to direct seeding and shorter growing seasons can take years to deliver results, even with new techniques such as “speed breeding”. Interruptions in funding can set programmes back to “square one”, Mirzabaev warns, because once breeding cycles are broken they cannot simply be restarted overnight.

Investment comes from a mix of sources. Development banks such as the World Bank and the Green Climate Fund are backing large-scale programmes in Vietnam and Thailand. Philanthropic bodies including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation support breeding work at IRRI and national research centres.

Private capital has so far been limited. Some exporters and food companies are beginning to explore “sustainable rice” branding, but the sector has yet to attract the kind of venture capital and private equity money seen in meat alternatives. The risk, IRRI experts warn, is that governments and investors underfund rice because of the abundant supply available today — only to find themselves unprepared when climate shocks push prices higher again.

http://ft.com/content/53f1a080-5dbb-499e-a6d1-5f39e1ff49c7Published Date: October 6, 2025