Tags

Basmati vs. Jasmine Rice: Here Are the Most Important Differences, According to Experts

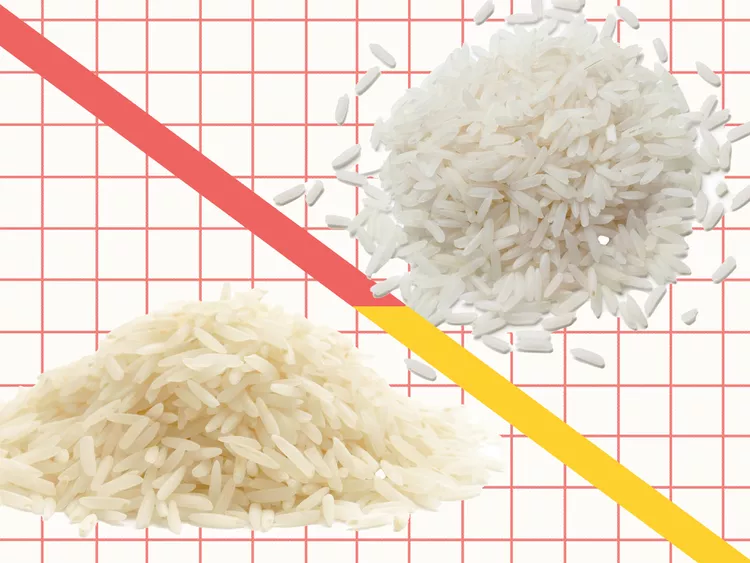

The two are more different than they are alike.

By Perry Santanachote

In This Article

- The Key Differences Between Basmati Rice and Jasmine Rice

- How Jasmine and Basmati Rice Are Traditionally Served

- Can You Substitute Jasmine for Basmati and Vice Versa?

- The Takeaway

For many cultures, a meal without rice is, frankly, not a meal at all. In Southeast Asia, jasmine rice tastes and—more importantly—smells like home. In South Asia and the Middle East, long, elegant basmati is the indispensable variety that graces the table.

Both jasmine and basmati rice are aromatic, long-grain varieties, but they have distinct characteristics in terms of flavor, aroma, texture, and culinary uses. The choice between them often depends on the dish you’re preparing, but what we love most about these two varieties is they are experts at dressing to suit the party. We spoke with fourth-generation farmer Brita Lundberg of California-based Lundberg Family Farms, Priyanka Naik, a chef, TV host, columnist, and author of The Modern Tiffin, and Pranee Khruasanit Halvorsen, a Seattle-based Thai cooking instructor, to learn more about the differences between these two beloved rice varieties and how to use them when cooking.

The Key Differences Between Basmati Rice and Jasmine Rice

Basmati and jasmine are long-grain, aromatic rice varieties. Both kinds of rice belong to the genus and species Oryza sativa, the scientific name for the Asian rice plant. Their subspecies is Indica, typically associated with long-grain, non-sticky varieties of rice that separate when cooked (unlike Japonica, a subspecies associated with stickier short-grain and medium-grain rice).

The similarities between basmati and jasmine rice mostly end there. A handful of key differences might inspire you to reach for one over the other.

Origin

Basmati rice originally comes from the Indian subcontinent—primarily India and Pakistan—while jasmine rice originated in Thailand. US basmati- and jasmine-type varieties are grown in California, Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Missouri. However, due to the unique environment of the Indian subcontinent, true basmati can’t be replicated on US soil.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1186262899-e4c4d6f822ec47cf9d26841c3c8453a3.jpg)

There are currently no patents or official DOP- or DOC-style rules (designation of origin) rules governing basmati or jasmine, so there are many hybrids grown in the US, such as California basmati and Texmati, to name a few.

In India and Thailand, basmati and jasmine seedlings are generally grown in a nursery and then transplanted by hand. In contrast, US farmers plant seeds directly into production fields, says Lundberg. Domestic basmati and jasmine also tend to behave differently than their imported counterparts. “Imported basmati rice will elongate during the cooking process, while most domestic basmati rice will not,” says Lundberg. And not all domestic jasmine rice is aromatic.

Aroma and Flavor

“Basmati and jasmine rice are both aromatic varieties, which means that as they cook, they fill the kitchen with an irresistible aroma,” says Lundberg. “Jasmine rice smells light and floral, while basmati rice has a nutty, popcorn-like aroma. Basmati rice has a subtle nutty flavor, while jasmine rice tastes sweet and buttery.”

Structure

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SEA-GettyImages-183328028-633bf4811b534c1793068b7ae7a27d3c.jpg)

Lundberg says both varieties contain amylose and amylopectin, which are starch components consisting of glucose molecules. Amylose is a straight chain structure that helps rice retain its texture. Amylopectin is a branched structure that causes the rice to be stickier and bind together. Basmati rice contains a larger ratio of amylose to amylopectin compared to jasmine rice, which gives basmati grains bite and structure and makes jasmine softer and stickier.

Texture

Lundberg says both rice varieties should cook up fluffy with distinct grains. Neither should be outright sticky, but jasmine is clingier than basmati.

Basmati rice grains are long, thin, and sharp at the ends when raw. When cooked, basmati rice will separate and grow twice as large. It has a firm, dry texture, and the grains’ ability to stay separate make them ideal for biryani, pulao (Indian rice and peas), and rice salads.

Jasmine rice grains are slightly shorter than basmati rice and a little more rounded at the tips when raw. This variety tends to be soft and moist when cooked, with kernels clinging together. It’s great for fried rice and served alongside curries and stir-fries.

Preparation

Both of these types of rice can be made on the stovetop. Rice cookers are better suited for making jasmine rice than basmati—the latter won’t cook up as fluffy in this type of appliance. And the stovetop is essential for crispy rice dishes like Persian tahdig, which is traditionally made with basmati.

In either case, rinse your rice before cooking it until the water runs clear. “Rice may be sold in the dry goods section of the grocery store next to pasta, but rice is a plant,” says Lundberg. “So, like produce, give your rice a good rinse. Rinsing rice also helps remove excess starch, giving your cooked rice a fluffy texture with separate rice kernels.”

Basmati rice benefits from a 30-minute soak, which hydrates the center of the rice kernel to help it elongate and cook more evenly. It’s cooked with a rice-to-water ratio of 1:1 to 1:2 (depending on the cooking method and how soft you’d like it) for about 20 to 25 minutes. Jasmine rice, on the other hand, is typically cooked with a rice-to-water ratio of 1:1.5, and takes 15 to 20 minutes to cook.

How Jasmine and Basmati Rice Are Traditionally Served

Basmati rice is most directly linked to Indian and other South Asian cuisines, but it’s also a go-to in many Middle Eastern cuisines, including Persian and Armenian. Try it alongside khadkhadi (coconut-tamarind shrimp), fesenjān (Persian meat braise), and vegetable qorma.

“How basmati is served varies by region, but my Southern Indian family’s dinner spread would have one green vegetable, one carby vegetable, like potatoes or root vegetables, one bean-type dish, and something soupy like yogurt-based stew or stewed lentils,” says Naik. “We’d have chapati, which is like a round flatbread, and of course, basmati rice.”

Basmati’s ability to absorb flavor and fluff up also makes it excellent for rice-based dishes in which the rice is infused with flavor, like pilaf, pulao, yogurt rice, and biryani. “Southern India is very rice-centric,” says Naik. “We literally have thousands upon thousands of rice dishes. With these rice dishes, the grains are sautéed with nuts, aromatics, and spices like peppercorns, cinnamon sticks, and turmeric.”

Jasmine rice is used in Thai cuisine as a main component of a meal, alongside curries, soups, and stir fries. Traditionally, this variety is considered a special occasion rice, says Halvorsen. “It’s a sophisticated rice, like a dish in and of itself, that you whip out for fancy meals,” she says. “When you make an impressive meal, you 100% have to finish it with jasmine.” Of course, you can use jasmine rice for quick meals like fried rice or as a side dish for lunch with vegetables and salted fish, but Halvorsen says any long-grain rice would be fine in those instances.

Jasmine is also integral to many other Southeast Asian dishes across Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and the Philippines. Try jasmine rice with bak kut teh (Malaysian pork rib soup), cơm tấm (Vietnamese broken rice), and cha kreung satch moan (Cambodian lemongrass chicken stir-fry).

Can You Substitute Jasmine for Basmati and Vice Versa?

“Discerning palates wouldn’t dare substitute jasmine for basmati, but as my dad says, jasmine and basmati rice are really more alike than they are different,” says Lundberg. “In a pinch, you can probably get away with substituting one for the other.”

We recommend going with the type of rice the recipe or cuisine calls for, but if you only have one type, it’s okay to swap them. “Jasmine and basmati rice are similar enough,” says Naik. “They have a little bit of a different fragrance, but I think they both go great with any sort of Asian cuisine.” Naik says she also uses basmati rice to make some Mexican dishes. However, if you’re making certain rice-based dishes like biryani or congee, the rice won’t cook up the same if you swap—jasmine will be too sticky for biryani, while the distinct grains of basmati will not achieve the porridge-like consistency of congee.

And as a side dish, you won’t be getting the full experience if you eat a Thai curry with basmati rice or an Indian curry with jasmine rice. “They just don’t go together,” says Halvorsen, pointing out that basmati is firmer, jasmine is softer, and the fragrances are different. And if you’re spending extra money to buy premium aromatic rices in the first place, it makes sense to use them the right way.

The Takeaway

Basmati and jasmine rice are both aromatic long-grain varieties, but they bring different qualities to the table. Jasmine offers a delicate floral fragrance with a hint of sweetness, while basmati has a rich, nutty flavor and aroma. Jasmine is also a bit softer and stickier compared to basmati, which has a fluffier texture and retains well-defined individual grains when cooked. We recommend sticking with the rice type suggested in the recipe you’re using, but you can enjoy either variety in many applications.

https://www.seriouseats.com/basmati-vs-jasmine-rice-8733489Published Date: October 25, 2024