Tags

Rice exports: lost opportunity

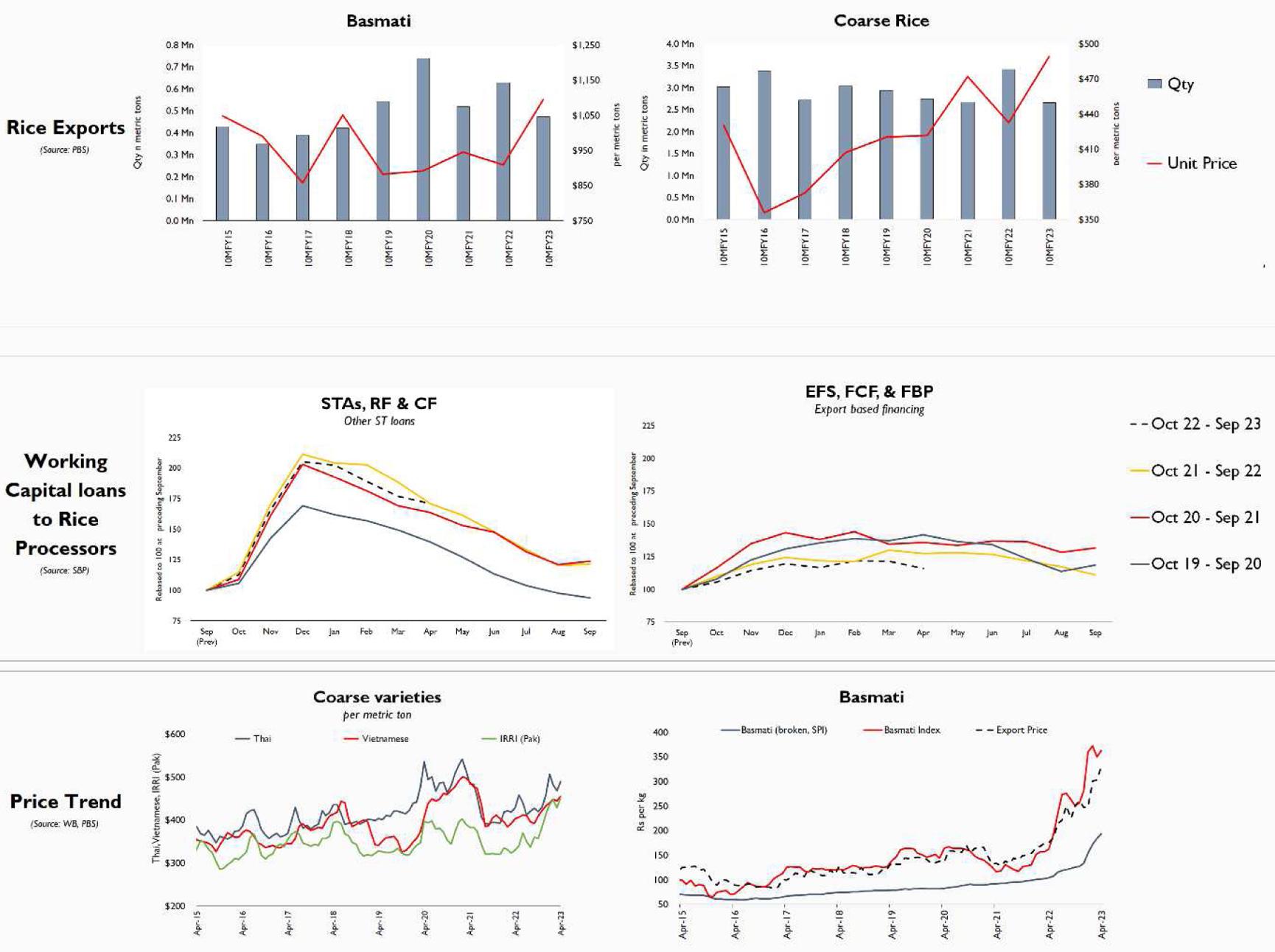

Earlier this month, the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) released the 10-month goods trade report card, laying bare the abysmal state of rice exports over the now concluding fiscal year 2022-23. Although many commentators have been quick to attribute blame for poor export performance to the devastating floods, there may be more to the story.

Regular readers may recall that forecast for national production during marketing year 2022-23 was lowered by 40 percent during last quarter of CY22 in the aftermath of devastating floods that affected cultivation of the crop in southern region of the country, but mainly in the Sindh province. Recall that crop production in Sindh is now responsible for nearly 30 percent of national output, of which over 90 percent are coarse rice varieties primarily geared towards the export markets.

Export of coarse rice varieties such as IRRI-6, IRRI-9, and hybrid rice contribute up to 75 percent of annual rice export revenue. In turn, coarse rice varieties constitute up to 85 percent of rice exports by volume, with the remainder contributed by export of the higher value basmati rice which contributes significantly lower volume. Thus, destruction of coarse rice crop in Sindh had put a major dampener in rice exports at the very onset of the rice marketing year, which begins in earnest upon harvest between Oct – Nov.

However, coarse rice varieties were never going to be the export play for calendar year 2023. After the resolution of short-lived frenzy from India surrounding rice export bans/duties upon delayed upward revision in the rice exporting giant’s domestic output, the pressure in the global trade markets had already eased to a major extent (especially in the H2-CY22). Remember, India alone contributes up to 40 percent of global rice exports (compared to 8 percent for Pakistan) and improved supplies there means more calm for rest of the world market. In fact, USDA estimates now suggest that world trade volumes have remained largely unchanged during MY22 and MY23, despite the price pressure and volatility witnessed for much of CY22.

Instead, for Pakistan – the bulk of export revenue were to stem from the export of significantly higher value basmati rice. Recall that basmati rice belt is predominantly situated in the north-eastern districts of Punjab province in the doab regions of Indus and its tributaries. As such, no widespread losses to basmati rice production were reported from northern and central Punjab districts in the aftermath of the 2022 monsoon floods.

Meanwhile, a significant upward swing in basmati prices in the western export destinations resulted in prices increasing by at least 50 percent during the ongoing marketing year (over the preceding 12-month period), that too in dollar terms. This rise at first followed an upward in demand post resumption of global commercial activity in 2021, and then due to tightened supplies from the only other exporting region – the Indian Punjab and Haryana states belt. However, basmati export quantum during the 10MFY23 from Pakistan has witnessed a seemingly inexplicable slump of 25 percent, declining 0.65 million metric tonnes (MMT) last year to barely 0.47 MMT during current fiscal year to date.

This slump especially comes as a surprise as it has been not been accompanied by any significant decline in local production. Meanwhile, basmati rice – which is the predominantly consumed variety in the local market –has witnessed prices in the domestic market already double over the last 12 months. This suggests that prices in the local market are fast adjusting to the rise recorded in the global market, but the absence of exportable surplus suggests that demand failed to weaken.

Of course, seemingly plausible explanations such as rising smuggling pressure from Afghanistan, Central Asian ‘stan states, and even Iran are presented to explain away the poor performance of official exports despite significant profit margin on offer upon exporting from official channel, given both higher prices fetched in western and Gulf destinations, the arbitrage offered by currency depreciation, and concessionary financing advanced by SBP on export of basmati variety only.

So, where in lies the truth? It is hard to know. One answer may be found in the oft repeated hypothesis that Pakistan’s actual basmati rice production is significantly lower than officially reported, which could explain why the astonishing rise in local prices amid record breaking inflation did not weaken domestic consumption. Another hypothesis offered by way of explanation is that smuggling from border regions may not necessarily offer higher profitability, but allows export of Pakistan’s (generally perceived) low quality basmati, which has higher aflatoxin and other contaminant levels – which would otherwise face high non-tariff barriers in the more sophisticated western markets.

It is hard to know where the truth lies. However, given the over 50 percent rise in basmati prices over last year, lower export market volume will indeed be remembered as a golden opportunity missed.

https://www.brecorder.com/news/40244328Published Date: May 26, 2023