Tags

How Women Farmers in the Sundarban Are Reviving Indigenous Rice Varieties.

Chandrima S. Bhattacharya

In a region hit hard by climate change, where salinity of agricultural land has become a major concern, indigenous rice varieties could bring some respite – provided farmers have the right support.

Sundarban (West Bengal): When Barnali Dhara, 50, stepped into her husband’s chemical fertiliser shop in Nischintapur, a locality in the Indian Sundarban, she was only trying to help her husband, who had got a job as a school teacher.

A store that sells chemical fertilisers – in Sundarban and elsewhere – is often a place where farmers meet and decide, at times together, which seed and which fertiliser to buy. In the Indian Sundarban, located in West Bengal, paddy is the main crop. Women work as much in the fields as men, if not more, but the decision of whether to buy hybrid, high-yielding paddy seeds and chemical fertilisers rests with the men.

Dhara knew that when she began to manage the shop in 2005. “I came from a Sundarban family of farmers, who were also teachers,” she says. She had passed the higher secondary (Class 12) board examination.

What she did not know was that after 12 years in the shop, her life would take a sharp turn.

“The men complained bitterly,” says Dhara. Nischintapur is located in Kulpi administrative block in West Bengal, not far from the Bay of Bengal. The farmers complained that the chemical fertilisers were reducing the fertility of the soil, and so the next season more fertilisers would have to be bought. In Sundarban, this adds to the precarity of a farmer’s situation.

The delta region that lies along the Bay of Bengal in India and Bangladesh is one of the most climate change-vulnerable places in the world. It experiences a sea level rise rate of about 8 mm per year, the world average being about 3.1 mm per year. In addition, cyclones, which are linked to climate change, have become almost annual events here.

May is a dreaded month. Cyclone Amphan had struck in May 2020, Cyclone Yaas in May 2021 and Cyclone Remal in May 2024. Cyclone Fani had hit Sundarban in April-end, 2019, and Cyclone Bulbul in November 2019. The saline water that floods in with cyclones and from sea level rise lead to salinity in the soil. This can render agricultural land uncultivable for years.

Saline deposits on Mousuni soil. Photo: Nishan Das

After Cyclone Aila in May 2009, which devastated the entire region, agriculture had stopped for four to five years in some places. “In Nischintapur, five years after Cyclone Amphan, someone’s land is still saline,” says Dhara.

But what stops growing in saline soil is the modern, scientifically developed hybrid variety of paddy that require chemical fertilisers. What survives is the indigenous or traditional paddy of Sundarban, a fact that was becoming increasingly clear after Cyclone Aila.

Yet farmers went on buying fertilisers for hybrid paddy cultivation. “At the same time they complained bitterly about rising debts,” says Dhara.

In 2017, Dhara enrolled herself at Ramkrishna Ashram Krishi Vigyan Kendra, an agriculture institute in Nimpith, about 35 km from Nischintapur, for a one-year course on organic farming. Today she is the chairperson of her company, Krishinirbhar Agri Farmers Producer Co Ltd., with its office a few minutes’ walk from the fertiliser store. The company promotes organic farming and is linked to about 2,000 farmers in Nischintapur and adjoining areas. “Of the 2,000, about 80% are women,” says Dhara. “Because almost all women are farmers in Sundarban.”

After her training, Dhara, a resident of Ashwatthatala village in the locality, approached a community of women in Nischintapur and nearby villages that she had herself organised, first by helping to form self-help groups, and later in 2016, by forming a larger women’s association, Ashwatthatala Janakalyan Mahila Samiti. She talked to them about organic farming and the women responded enthusiastically.

From 2018 – her company would be formed in 2023 – Dhara began to organise for women farmers from the area to attend courses on organic farming at the Nimpith institute. “So far about 15 to 20 batches of 30 women farmers have gone to the institute. This will continue,” says Dhara.

The training proved life-changing for the women farmers. They are mostly small, marginal farmers. Some are landless. For the first time, at the training, they were defined by their work. It helped them find a voice at home. Many of them were able to convert their households to organic farming, at least to a degree.

Dhara’s company helps farmers with training and selling their produce. “Of the 2,000 farmers associated with the company, about 580 are shareholders and the rest have linkages with us,” says Dhara, who received the President’s Award in 2025. The ‘linkage-chashis’, who are not shareholders, are helped with organic inputs for agriculture, training and marketing of their produce by the company.

Her work has created other champions. Anjali Ghosh, 49, of Arunnagar village, vowed never to touch chemical fertilisers and pesticides after her training at Nimpith and Anand, Gujarat. “Ami beesh byabohar kori na (I never use poison),” says Ghosh.

She grows Dudher Sar rice, an indigenous rice that is Sundarban’s favourite, and vegetables, selling the surplus. She has five cows and uses the cow dung as manure and a neem-based pesticide. At Nimpith, the women were taught to prepare compost and vermicompost for the soil and use trichoderma viride and pheromone traps to control pests.

But the centrepiece of Ghosh’s 2.5 bighas of land is a biogas plant that produces fuel using cow dung. Her kitchen runs on this. Her husband, who would once migrate for work when he felt fitter, works alongside her. She is a self-reliant, confident and assertive woman.

Anjali Ghosh and Barnali Dhara at the biogas plant. Photo: Nishan Das

Pramila Jana, 50, a resident of Bajberia village nearby, also trained at Nimpith. “I never use any chemical,” she says proudly. She grows Dudher Sar rice and vegetables on her five bighas. It is a very hot afternoon in April – Sundarban is experiencing a steady rise in temperature on land, as well as on the sea surface – and she has been working in the fields. The vegetables she has grown – chillis, pumpkin, puin shak (Malabar spinach) – come in strikingly bright shades. “I also grow broccoli, purple cabbage and yellow cabbage,” she says.

Brajalata Dolui, 38, also a resident of Bajberia and trained at Nimpith, says chemical fertilisers did not help to reduce the salinity of her land after Amphan. She cultivates Dudher Sar and vegetables on her four bighas with her husband, who would migrate for work earlier. She works in the fields from early morning, goes to the market to sell vegetables, manages all household work and goes to the fields again in the evening.

Pramila Jana (L) and Brajalata Dolui. Photo: Nishan Das

Calculating how many hours a woman farmer works is another matter. But not Nischintapur alone, the whole of Sundarban is waking up to the possibilities of the resilience of indigenous paddy and organic farming as a survival strategy in the face of climate change – and women are at the forefront of this change.

Lost and found

Women as farmers of indigenous paddy are not new in Sundarban. When cultivated as the Aman (monsoon) crop, with good rainfall, indigenous varieties may not need any external input such as fertilisers or pesticides. Since this means less labour, women were traditionally assigned to such cultivation.

The number of women in agriculture increased significantly after Cyclone Aila in 2009, when the men migrated in large numbers, spurred on by loss of agriculture due to salinity. This was believed to be the biggest wave of migration in recent years from the Indian Sundarban, especially of men and boys, for work.

Of the about 9,60,000 hectares covered by the Indian Sundarban, about 3,15,500 hectares are cultivable land, according to the website of Sundarban Affairs department, West Bengal government.

“Paddy cultivation is 90% of the total agricultural production during Aman (monsoon) season,” a Bengal government official said. Paddy is cultivated less during the Boro (winter) season.

After Cyclone Aila, women in many households took on the responsibility of full-fledged farm work along with household work and other social and familial responsibilities.

About the same time, a conscious effort to cultivate indigenous paddy began as its climate-resilient features became evident. But most indigenous varieties had been forgotten for decades since the introduction of modern varieties.

“Once West Bengal had more than 5,000 varieties of indigenous rice, but now we find barely 150 varieties that are being cultivated,” says Anupam Paul, former additional director of agriculture (personnel), Directorate of Agriculture, Nadia, West Bengal. As assistant director of agriculture, Agricultural Training Centre, Fulia, Nadia, where he spent 20 years of his service life, he collected and conserved more than 400 varieties of indigenous rice so far.

The Green Revolution had promoted chemical fertiliser-tolerant modern paddy and wheat at the expense of traditional crops. “This idea of agriculture was based on productivity alone. It also promoted monoculture, which is bad for soil and crops, and ignored the nutritional and low-cost benefits of indigenous crops,” says Paul. Kalabhat, for example, is a highly nutritious paddy variety.

“Application of chemical fertilisers, especially nitrogenous fertilisers, made the crop more vulnerable to pests, which increased the use of pesticides,” he explains. These effects began to be felt in Sundarban from the 1980s.

Amales Misra, a retired scientist of the Zoological Survey of India, has also been working tirelessly to conserve Sundarban’s indigenous paddy.

Misra, who is from Sagar block in Sundarban, has founded Amargram Pupa, an NGO in Sagar. In its premises he has been building a seed bank of indigenous varieties of paddy, for which he has collected more than 150 varieties of grain so far. More than 120 of these are from Sundarban.

On the way to Sagar Island. Photo: Nishan Das

“Dadsal, Dudher Sar, Tangrasal, Khejurchari and Hyangra are a few of the indigenous salt-tolerant varieties from Sundarban,” says Misra. Other indigenous paddy shows other kinds of resilience, though there may be overlaps. After Cyclone Bulbul in November 2019, the water level in the paddy fields went up to more than two feet, but a few varieties still stood upright. These included Binni, Dokrapatnai, Kalabhat, Malaboti, Patnai and Talmugur, says Misra.

The varieties that can withstand high-speed wind include Tangrasal, Hogla, Sadamota, Patnai and Dokra.

“Different places in Sundarban grow different indigenous paddy varieties,” says Anirban Roy, assistant professor, genetics and plant breeding, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda Educatioal and Research Institute, Narendrapur. “Kanakchur grows in Mathurapur, Lakshmikantapur and Jayanagar, Gheus in Gosaba and Harinapuri in Patharpratimaa and Sagar.”

“But a traditional south Bengal variety called Guligati, however, which could tolerate stagnant water of one foot or more for 25-30 days, is lost forever,” says Paul.

Research is being conducted at the Postgraduate and Research Department of Biotechnology, St Xavier’s College (Autonomous) Kolkata, in collaboration with Amargram Pupa, to identify climate-resilient paddy varieties indigenous to Sundarban with the objective of reintroducing them to farmers.

“The 11 varieties collected and identified so far are Bhutmuri, Tangrasal, Talmugur, Hyangra, Hogla, Kalabhat, Nona Bokhra, Aman Banshkatha, Aman Dehradun Gandheswari, Taladi Nona and Shatia,” says Sayak Ganguli, assistant professor at the department. “A crop variety is considered indigenous if it has grown for at least 30 years in a particular ecoregion using traditional farming practices,” he explains. “It means it has established itself there.”

The method adopted by the research team also demonstrates that indigenousness is not an absolute state. If the story of Sundarban’s people is one of migration and adaptation – the largest human settlements here occurred during the colonial period – the story of its paddy is also one of migration and adaptation.

Paul thinks a few Sundarban salt-tolerant varieties, Nona Bokhra, Talmugur or Kerala Altapati, are from Kerala.

On the way to Mousuni island. Photo: Nishan Das

Grow from seed

At the ground level, this knowledge is being nurtured often by women, through the preservation of seeds and other practices.

Seeds are grown from indigenous paddy by farmers. That is not possible with modern, developed varieties, for which seeds have to be bought.

Rupantaran Foundation, a non-profit organisation that was working with children and youth in Sundarban since Cyclone Aila in 2009, has been helping women farmers in Sundarban to grow indigenous paddy since Cyclone Amphan in 2020. They distribute Dudher Sar seeds on a large scale, which they often obtain from women farmers.

Relief work in Sundarban after Cyclone Amphan had been a revelation for the Kolkata-based organisation. “We noticed that hardly any men stood in the queues for relief,” says Smita Sen, founder and executive director of Rupantaran. Men felt it would hurt their dignity to be seen asking for help.

“We began to ask women what would give them dignity,” says Sen. The women did not want standard relief materials, more food or clothes. “They wanted chun (lime powder) and shorsher khol (mustard cakes) to reduce the salinity of their agricultural land,” says Sen. They all worked in the fields, even if they rarely called themselves farmers.

Rupantaran decided to shift its focus to women, by beginning to form women’s groups across five blocks in Sundarban, including Namkhana and Patharpratima, and distributing indigenous seeds. “But we are not a livelihood-based organisation. We are a gender-based organisation,” insists Sen. The idea was to bring women together.

Sometimes the indifference of men helps. A member of one of the organisation’s groups in Namkhana village in Namkhana block laughs as she recounts how she could try organic farming. The soil was too saline after Cyclone Amphan and there was nothing to lose by indulging her, her husband felt. But when vegetables grew well with indigenous seeds in 2021, and Dudher Sar paddy was successful in 2022, the family moved to organic farming.

Dudher Sar is moderately salt-tolerant, but the short-grained and fine-textured rice – its name means milk cream – is the star among indigenous Sundarban paddy.

Almost 13,000 women farmers are members of groups created by Rupantaran in the five blocks now. A substantial number of them cultivate Dudher Sar as the Aman crop.

Meera Khatua (L) and her home. Photo: Nishan Das

But the paucity of paddy seeds is a problem, given the scale of cultivation. “These are often found with the women farmers, who keep the seeds,” says Sen.

Mousuni in Namkhana block is a southern tip of Sundarban slowly disappearing into the sea. The sea level rise rate here is 12 mm per year.

It was battered by all the cyclones, but during Cyclone Yaas it was inundated by floodwater, from which it is still recovering.

Meera Khatua, 61, who is still working on her 1.5 bighas at 11 am on a hot April day, goes inside her mud hut in Mousuni island in Namkhana block and shows several varieties of seeds that she is preparing. She grows rice, potatoes, onions, brinjals, beans and leafy vegetables. Her hut and its doorways are lined with onions hanging from above, like decorations. She has grown them and they will remain fresh this way. At the house of Feroza Bibi, 50, tomatoes are hung in a similar way with their stems intact to retain their freshness for a period of time.

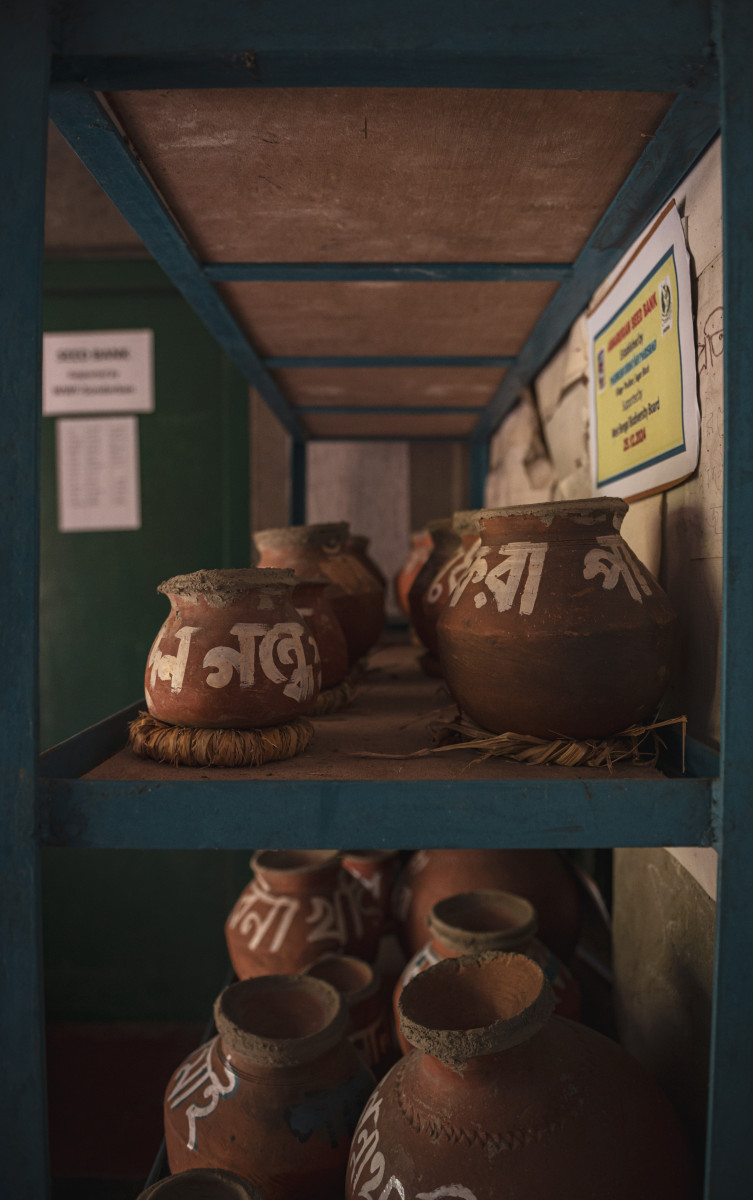

The Amargram Pupa Seed bank. Photo: Nishan Das

Seeds need drying, tending and watching for an entire season, before they are sown. This becomes the work of women.

The seed bank at Amargram Pupa, which distributes indigenous paddy seeds to women farmers in Sagar villages and works with groups of women farmers to encourage organic farming, is located in the premises of the organisation at Phulbari village on Sagar island and is looked after by women. It consists of two shelves lined with earthen pots with the names of the paddy varieties written in white on them – a sight for sore eyes and ears, as the names usually are evocative. Sagar island, also an administrative block, is another southern tip of Sundarban exposed to the sea and has been damaged extensively by the cyclones and sea level rise.

Though Misra has been collecting the indigenous paddy seeds, including rare varieties such as Bhunri, the seed bank is managed by Sudipti Haldar, 53, and Susmita Bhuiyan, 41. Another lot of seeds is kept in a room inside.

Haldar is in charge of maintaining the seed bank. Bhuiyan works with the seeds, planting each variety once a year in narrow strips in the “demo” agricultural field within the premises of the organisation, keeping them alive.

Many scientific experiments are being conducted by institutions on these small stretches of land with small squares of numerous varieties of paddy, indigenous and hybrid. Their features are being studied as well as comparisons are being made between the effects of chemical and organic fertilisers and pesticides on them. The women carry out this work.

Collectives help women to speak in the same voice. But individually, too, and in other contexts, women from Sundarban talk about the urgency of shifting from chemicals. Diseases have gone up, they say, and link it to the use of chemicals.

At a meeting of residents from 10 villages in Joygopalpur in Sundarban’s Basanti bock, a cyclone-devastated area, several women, when asked about the loss and damage experienced from climate change-related events, spoke about the immediate need to turn away from chemicals. They said women, including younger ones, are experiencing the increased occurrence of tumours and ovarian and uterine cysts, which they feel is linked to the chemicals at home.

At a health camp organised by UNICEF In Lahiripur in Gosaba sub-division, among the areas hit worst by cyclones, women expressed the same worries.

At a cyclone shelter in Mousuni, at a meeting of 17 women farmers from Rupantaran groups, Anjali Das Santra, 34, who passed the higher secondary examination, chuckles as she recalls what she told her in-laws after Cyclone Yaas. She was convinced that chemical fertilisers would not drain the salinity from the soil; cow dung manure would. “I said, I have watched you play so long, ebar amar khela ta dekhun (now watch my game)!” Later, from the embankment, she points at the edge of the water. “That was where my husband’s family home was ten years ago,” says Das Santra. “About five bighas that belonged to my in-laws are submerged now.”

Anjali Das Santra’s home stood here in Mousuni, now under water. Photo: Nishan Das

Never say die

The women’s counsel, however, works only for the Aman season in most cases. The spectre of chemical farming always looms large.

Many households, even if they practice several organic farming methods, may use small amounts of chemicals. Vegetables such as brinjals, ladies fingers, tomatoes and bitter gourd, prone to pest attacks, are often treated with chemical pesticides.

Misra points out that a farmer with an aal (boundary) around the field may use chemical fertilisers during Aman crop as well. The aal will prevent the water-soluble chemical from flowing out.

Any chemical used during the cultivation stops crops from being organic, perhaps for seasons to come.

But the bigger reason behind using chemicals is livelihood. Ironically, that is also a response to climate change. The Boro paddy crop illustrates this perfectly.

In Sundarban, the rain-fed indigenous Aman paddy crop, tasty and nutritious, though generally not high-yielding, often takes care of the family’s requirement. But with increasing climate vulnerability, including scanty or excessive rainfall, households want to ensure greater food security and financial security.

Paddy as a Boro crop is being cultivated significantly more in Sundarban in the last few years with this aim. Since the winter months are dry, the natural choices are the hybrid, high-yielding paddy varieties cultivated with chemicals.

They are also cultivated using huge stores of groundwater, which is creating an acute water crisis in many parts of Sundarban, leading to an illegal, private water-selling business using up more groundwater. The second paddy crop is creating crop monoculture. And even after all this, the crop may not survive a cyclone. Boro paddy in Sundarban ticks all the wrong boxes.

Yet farmers are taking all these risks, because they have no choice in the face of an uncertain future.

A farmers meeting at Mousuni. Photo: Nishan Das

Boro cultivation also sees a greater participation from men. Before winter, many men who had migrated come back to stay for a few months that are to be utilised in planting a hybrid “lucrative” crop. The conversation goes back to the fertiliser store.

Many, including sections of farmers, want an end to the Boro paddy in Sundarban. “But what can farmers do? Do they have any alternative?” asks Sudipta Tripathi, assistant professor, School of Environment and Disaster Management, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda Educatioal and Research Institute, Narendrapur.

Cultivation of pulses and vegetables during winter, which was traditional in Sundarban, may be an answer, but these have to be viable in the market.

Anirban Roy, Tripathi’s colleague from Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding, points at the rationale behind choosing Boro paddy: the difference in production volume between indigenous and hybrid, high-yielding varieties.

“Indigenous varieties yield about 2.5 tonnes per hectare. High-yielding varieties yield 4-7 tonnes per hectare,” he says. “Dudher Sar yields about 2 tonnes per hectare.”

The volume ensures that hybrid, high-yielding paddy can be sold in the market, unlike much of the indigenous paddy.

Experts, however, question how “lucrative” high-yielding crops are, given the high costs of their production that requires seeds, fertilisers and pesticides. “It may go up to Rs 5,000 per bigha,” says Dhara. Tractor use and employment of farm labourers may cost another Rs 10,000. “A bigha produces about 10 quintal paddy in a good season, that is bought at approximately Rs 2,400 per quintal,” she says. It leaves the farmer with a thin margin of less than Rs 10,000 per bigha in a season for profit.

Studies also question the greater efficacy attributed to chemical fertilisers and pesticides over their organic counterparts.

Several government schemes address the Sundarban. The Union government has launched its Paramparagat Krishi Vikash Yojana to promote organic cultivation in three Sundarban blocks. The Department of Sundarban Affairs, West Bengal, has recently distributed 5,000 units of portable vermibeds to marginal farmers of Sundarban, a department official says. The department has also set up Sundarini, an all-women farmers’ co-operative that focuses on dairy products, in Sundarban.

Becharam Manna, minister-of-state in charge of Agricultural Marketing Department, West Bengal, mentions the Comprehensive Area Development Corporation (CADC), which markets organically produced indigenous paddy and other farm productions by women from the state.

But the state has to intervene at the point when the farmer is being compelled to turn to the chemical fertiliser. “Farmers want to change, but cannot. The reasons are socio-economic, socio-political. The true superiority of the indigenous paddy has to be established,” says Ganguli.

A mechanism that would give indigenous crop producers more access to the market, ensuring prices that are acceptable for both farmers at one end and consumers on the other, has to be in place. In Sundarban, this would at once be a step towards climate action and women’s empowerment.

https://m.thewire.in/article/agriculture/how-women-farmers-in-the-sundarban-are-reviving-indigenous-rice-varieties/ampPublished Date: May 15, 2025