Tags

Explained: Why farmers prefer growing rice and wheat

The reason isn’t assured MSP procurement alone. It is also because of the two cereal crops receiving priority in public breeding and research support, reflected in steady yield increases over time.

Written by Harish Damodaran.

Farmers, like all businessmen, are rational and risk-averse. Everything else being the same, they will choose to grow crops that offer reasonable price as well as yield assurance.

No surprise, then, that rice and wheat are their most preferred crops – more so when they have access to basic irrigation that can supplement natural rainfall.

Between 2015-16 and 2024-25, the area planted under rice has increased from 29.8 to 32.4 lakh hectares (lh) in Punjab, while from 10.5 lh to 47 lh in Telangana. Both wheat and rice acreages in Madhya Pradesh have, likewise, gone up from 59.1 lh to 78.1 lh and from 20.2 lh to 38.7 lh respectively over this 10-year period.

The most obvious explanation for the above expansion in rice and wheat area is the government’s near-guaranteed purchases of the two crops at minimum support prices (MSP).

This kind of government backstop does not exist for other crops, discouraging their cultivation, save in years when market prices are good. Thus, Punjab’s cotton area has plunged from 3.4 lh in 2015-16 to one lh in 2024-25. It rose from 17.7 lh in 2015-16 to 23.6 lh in 2020-21 for Telangana, only to fall to 18.1 lh in 2024-25.

In MP, area under chana (chickpea) has declined from 30.2 lh in 2015-16 to 20.1 lh in 2024-25. So has it under soyabean (from 59.1 lh to 57.8 lh), after touching 66.7 lh in 2020-21 when prices went through the roof.

Not prices alone

But it isn’t just MSP assurance that makes farmers more inclined to plant rice and wheat.

No less significant is yield risk, which is relatively less in the two crops because of their being grown largely under irrigated conditions and also receiving priority with regard to public breeding and research support.

Take wheat. The traditional tall varieties with slender stems yielded only 1-1.5 tonnes of grain per hectare. The new Green Revolution varieties were semi-dwarf with strong stems and didn’t “lodge” – bend over and even falling flat – when their panicles or ear-heads were heavy with well-filled grains. Being non-lodging made them more responsive to fertiliser and water application.

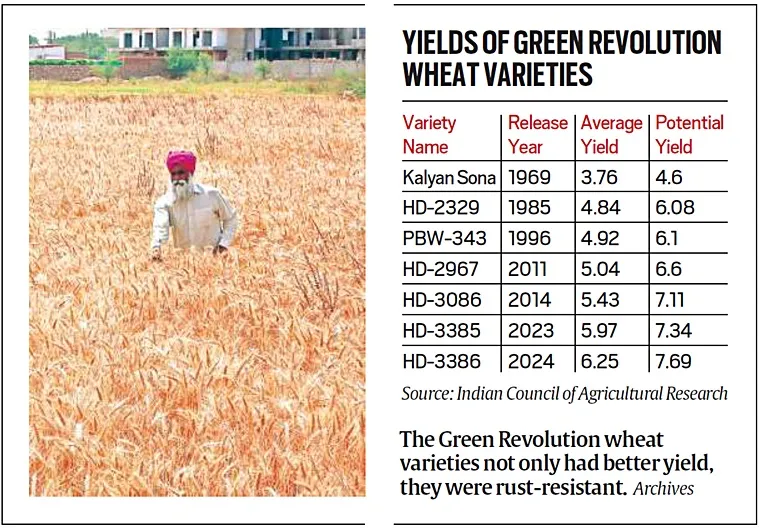

The first generation of Green Revolution wheat varieties such as Kalyan Sona and Sonalika, released in the late-1960s, yielded an average 3.8 tonnes of grain per hectare under normal growing conditions in farmers’ fields. Potential yields – the maximum realised under trial conditions with perfect weather, no pest or diseases, and ample supply of nutrients and water – were 4.6 tonnes.

The accompanying chart shows a steady increase in wheat yields, both average and potential, through successive varieties developed even after Kalyan Sona. These were bred for not only higher yields, but also for resistance against rust diseases (caused by fungal pathogens) and climate-smart traits.

The HD-3385 variety released in 2023, for example, yields an average of 6 tonnes per hectare and potential of over 7.3 tonnes. It is, moreover, resistant to all major rusts – yellow (stripe), black (stem) and brown (leaf) – and can be sown early (October 15 to November 2-3) as well as normal time (November 4-25) and late (after November 25). Amenability to early sowing reduces the risk of the crop being exposed to temperature spikes in March at the final grain formation and filling stages.

More grain in less time

In rice, too, yields have risen over time. The traditional tall varieties produced 1-3 tonnes of paddy (rice with husk) per hectare over 160-180 days duration from seed sowing to grain harvesting.

IR-8, the first ever semi-dwarf rice variety released in late-1966, yielded 4.5-5 tonnes/hectare over just 130 days. Samba Mahsuri (BPT-5204), released in 1986, gave an average of 4.5 tonnes with a potential yield of 6.5 tonnes.

Earlier this month, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) unveiled a genetically-edited (GE) mutant line of Samba Mahsuri. It has been developed by “editing” a gene coding for an enzyme that suppresses cytokinin levels in rice. Cytokinins are plant hormones that help increase the number of grains per panicle. ICAR scientists have basically used CRISPR-Cas GE technology to cut and modify the DNA sequence of the said ‘Gn1a’ gene, in order to reduce its expression and promote cytokinin accumulation, leading to higher grain numbers.

The new GE mutant, called Kamala, produces 450-500 grains per panicle, as against 200-250 grains in the parent Samba Mahsuri variety. The result is not only higher average and potential yields of 5.37 tonnes and 9 tonnes per hectare. Kamala also matures in 130 days, 15-20 days earlier than Samba Mahsuri. Lower duration translates into water savings. Kamala also has more root biomass area, which enhances the plant’s ability to mobilise available phosphorous and nitrogen in the soil for its growth and development. That, in turn, helps save the use of urea and phosphate fertilisers as well.

ICAR scientists have used CRISPR-Cas technology to similarly “edit” a DST (drought and salt tolerance) gene in another popular rice variety, Cottondora Sannalu (MTU-1010). The DST gene acts as a negative regulator, inhibiting the rice plant’s tolerance to abiotic stresses such as heat and salinity. Reducing its expression through editing, then, makes cultivation of Cottondora Sannalu – the GE mutant line of this variety is called Pusa DST Rice 1 – viable even under conditions of water, salinity and alkalinity stress.

Implications for other crops

In short, continuous breeding improvements in wheat and rice – focusing on raising yields, resistance to diseases and pests, resilience to abiotic stresses from drought and salinity to extreme temperatures, and lowering of maturity periods – have increased the attractiveness of growing the two crops. This is on top of the assured MSP procurement and access to irrigation, whether through canals or groundwater, they enjoy.

Other crops haven’t received the same extent of agricultural research and development support. Cotton has seen no new breeding breakthroughs after the genetically modified (GM) Bt cotton hybrids commercialised during 2002-06.

Since then, no new GM event (entailing the introduction of genes from unrelated species into host plants) has been approved, be it in cotton, mustard or brinjal.

While yields in most oilseeds, pulses and other field crops have been flat or registered modest increases, this isn’t the case with rice and wheat. In rice, there are hybrids today that give up to 10 tonnes/hectare yield within 120-125 days duration. And with direct seeding technology – requiring no nursery sowings, transplantation of seedlings and flooding of fields – there is further saving of water along with labour.

The economics, in terms of yield and price stability, aren’t as favourable in other crops. And that’s showing in their fluctuation acreages too.

https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-economics/explained-why-farmers-prefer-growing-rice-and-wheat-9996906/

Published Date: May 12, 2025